A Further History of the Library

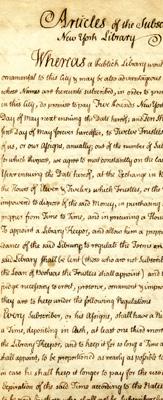

In March 1754, six public-spirited young New Yorkers—William Alexander, John Morin Scott, William Smith, and Philip, Robert and William Livingston—conceived the idea of establishing a "useful as well as ornamental" library in the city of New York. Interesting a number of their friends, they succeeded in selling more than a hundred shares at five pounds each, with yearly assessments of ten shillings.

Lieutenant Governor DeLancey and the Common Council approved the plan and permission was given to use a room in City Hall. In this room had been stored gifts of books, mainly theological, received from the Reverend John Sharp and from the estate of the Reverend John Millington, both of whom had been interested in establishing a public library in the colony. These became part of the new library.

At a meeting held on April 30th at the Exchange Coffee Room on Broad Street, the following twelve trustees were elected: Lieutenant Governor James DeLancey, James Alexander, William Alexander, the Reverend Henry Barclay, John Chambers, Robert R. Livingston, Joseph Murray, Benjamin Nicoll, William Peartree Smith, William Walton, and John Watts.

The New York Society Library was the name chosen for the new organization although it was generally called the New York Library until 1759. The word "society" was not then used in a social sense and the liberal founders had no thought of exclusiveness. They said: "The rights and privileges in the said Library shall not be confined to this city, but that every person residing in this province may become a subscriber."

Following the first official meeting of the trustees on May 7, 1754, books were ordered from London and in October the new library was launched. Benjamin Hildreth was appointed Library Keeper to attend every Wednesday afternoon from two to four, at a salary of six pounds per annum. Books were lent for certain periods according to their size—a folio for six weeks, a quarto for four, an octavo for three, and a duo-decimo for two.

The Library prospered and in 1772 applied for and received a charter from King George III. The resolution with signatures, the rough parchment draft of the charter, the beautiful parchment document itself, and the bill for engrossing it are among the Library's treasures today.

The minutes of the New York Society Library continued to record progress until May 9, 1774, after which follows this laconic entry: "The accidents of the late war having nearly destroyed the former Library, no meeting of the proprietors for the choice of Trustees was held from the last Tuesday in April 1774 until Tuesday ye 20 December 1788."

In 1789, the Legislature confirmed the Library's charter and the Common Council again voted the use of a room in what is now called Federal Hall. More shares were sold and more books ordered from England.

As the first Congress was then meeting under the same roof, and library privileges were conferred upon its members, the New York Society Library functioned as the first Library of Congress.

The first charging ledger contains evidence that President George Washington sent in one day for Vattel's Law of Nations and a volume of debates of Parliament, perhaps to settle some of his new problems, and John Adams came in person for Kames's Elements of Criticism.

Other pages of the old ledger list the books borrowed by Aaron Burr, DeWitt Clinton, Nicholas Fish, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Rufus King, James Roosevelt, and many others whose names are part of our country's history.

By 1793, the Library had grown to 5,000 volumes and needed a building of its own. A plot of ground was leased and a building constructed at 33 Nassau Street, where the Guaranty Trust Company of New York formerly stood.

In 1840, the Library, having combined with (later absorbing) the New York Athenaeum, a literary and scientific club of the day, moved into its second building, a handsome, roomy edifice with Ionic columns at the corner of Broadway and Leonard Street. In the same year, the Library was opened to temporary subscribers at the rate of ten dollars for one year, six dollars for six months, and four for three months.

This was a lively period, for a large lecture room was the scene of entertainments, discussions, and assemblies of the widest variety. There were lectures by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe, readings by Fanny Kemble and Anna Cora Mowatt, performances by the Swiss Bell-ringers and Campbell's Minstrels. Odell's Annals of the New York Stage contains a wealth of information about the activities of the Library in those years.

A Visitor's Book kept from 1836 to 1855 records distinguished visitors from all parts of the world and cities all over the United States. Among them were: Prince Bonaparte (afterward Napoleon III), James Fenimore Cooper, Charles Dickens, Francis Parkman, Prince Paul of Wurtenberg, Sir Robert Peel, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Martin Van Buren, to name a very few.

In 1853, the Library sold its building to D. Appleton and Company and moved into temporary quarters at the Bible House while awaiting completion of a new building at 67, later numbered 109, University Place, between Twelfth and Thirteenth Streets. This was occupied in 1856 with a collection of about 35,000 volumes and it remained the Library's headquarters for eighty-one years.

The Library had received its first legacy in 1849 of five thousand dollars from Miss Elizabeth DeMilt. It was followed by other bequests, and in 1917 came the generous one of the residuary estate of Mrs. Charles C. Goodhue, intended for a building to house the Library and the objets d'art which were part of the legacy. In 1936, judicious investment having more than doubled the fund, the house at 53 East 79th Street was purchased and appropriate alterations made. The Library moved into it in July 1937, with a collection of more than 150,000 volumes.

In 1952, the Library was among the many fortunate beneficiaries of the estate of Mrs. H. Sylvia A.H.G. Wilks, daughter of Mrs. Hetty Green. In 1973, Emil J. Baumann left the Library another substantial bequest. A fundraising campaign in the 1980's resulted in other gifts. Thanks to these legacies and donations and to careful financial management, the Library has a sound economic foundation.

The trustees ceased to issue regular certificates of membership in 1937 except to qualify new trustees, as required under the charter. But, after 1984, shares could be issued in exceptional cases of benefaction to the Library.

From the start, the Library has been exceptionally fortunate in its leadership. Trustees of literary interest, experience, and judgment in each generation have served on the Board. Many have been descendents of the original trustees. A glance at the distinguished names from the past show Hamilton Fish Armstrong, John Bigelow, Anthony Bleecker, John Romeyn Brodhead, John Mason Brown, William Allen Butler, Beverly Chew, Evert A. Duyckinck, Hugh Gaine, Washington Irving, Peter A. Jay, Robert Lenox Kennedy, James Kent, Rufus King, Walter Millis, Clement Clark Moore, Frederic de Peyster, John Pintard, F. Augustus Schermerhorn, Baron Steuben, Henry C. Swords, Richard Varick, Gulian C. Verplanck, John Watts, and others.

Although the Library has lived through many wars, only the Revolution interrupted its activities. Even then, someone's care and forethought preserved the old minute books as well as the John Sharp books. It is thus that the Library still possesses the record of its history from the beginning and a part of the first public library in New York. Other special collections include the Winthrop Collection, nearly 300 volumes that belonged to Connecticut governor John Winthrop, Jr. (1606-1676), on such topics as law, theology, medicine, and alchemy; the Hammond Collection of popular literature from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; and the John C. Green Art Collection.

The Library is rich in Americana—books, pamphlets, and some autograph letters from prominent Americans—but most especially in biographies and in travel accounts of the 19th century.

The unique collection of Library records is a source of interest to historians and biographers. The charging ledgers listing books borrowed from 1789 to 1907, when ledgers were replaced with cards, have helped researchers trace the course of reading interests and supplied information for biographies.

The membership lists contain such colorful names as John Jacob Astor, W.H. Auden, John James Audubon, Samuel Barber, John Jay Chapman, Willa Cather, Clarence Day, Jr., Simon Flexner, Eliza Jumel, Lillian Hellman, Herman Melville, Edward Stelchen, Alexander T. Stewart, and Norman Thomas.

In 1850, the Library held 31,000 volumes, in 1900 the collection reached 100,000 volumes; but by the mid-1980's the collection had close to 200,000 books, many of these being out of print and unobtainable in most city libraries. Today, the library has over 275,000 books.

From 1980 to 1984, the Library building was renovated in its entirety. Centralized air conditioning, modern lighting, improved research facilities, controlled humidity and temperature for book storage areas, and newly furnished children's and reading rooms were made available.

In 2010, thanks to four philanthropists, the Library did more renovations. It installed a Handi-Lift in the entry hall to make it handicap accessible. It renovated the entire Fifth Floor, which markedly increased seating in the newly named Hornblower Room and created six individual study rooms. It also restored a magnificent leaded skylight above the main staircase.

The present services and facilities of the Library, as well as conditions for use, are described in Use of the Library: Terms and Rules available at the circulation desk. The history of the Library was authoritatively recorded by Austin Baxter Keep in a volume published by the Trustees in 1907. Marion King, who had served the Library for many years, took up the tale in Books and People, published in 1954 by the Macmillan Company in honor of the Library's Bicentennial.

Serving both the casual reader and the scholar, the Society Library is in the second half of its third century of operation maintaining its mission of creating a Library available to the public that will be "ornamental... and advantageous" to New Yorkers.