He'll Go Up to Posterity: Guy Fawkes in the Stacks

Remember, remember

the Fifth of November

the Gunpowder Treason and Plot

I know of no reason

the Gunpowder Treason

should ever be forgot

On the night of November 4, 1605, searchers surprised one Guy Fawkes in a storeroom under the Palace of Westminster. The storeroom was full of barrels of gunpowder, Fawkes’ pockets were full of fuses, and the intent had been to blow up the building complex on November 5, slaughtering most of Parliament and the royal family. A small and non-representative band of English Catholics were revolting in full King Ralph style. Within hours of the plot’s thwarting, the government was turning the conspiracy to its advantage. From this, an oddly enduring day of remembrance has carried on down the centuries – or not so oddly, perhaps, since the Anglican church officially gave thanks for deliverance each November 5 until 1859.

Guy Fawkes Day, or Bonfire Night, was a cherished English holiday until recently and is still celebrated in many places today, often overlapping with the costumes and candy of Halloween or the solemn commemmorations of All Saints and All Souls. In the United States, Fawkes might be best-known from Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta and the playful name of Professor Dumbledore’s phoenix familiar in the Harry Potter books. But a hunt through our history-rich book cellars turns up quite a few treatments and angles on the events of the Fifth of November.

A brief dip into the literature has taught me that

The date should really be named for Robert Catesby, the charismatic chief plotter who just didn’t happen to be on the premises for the bust. But who’d ever remember remember Robert Catesby Day? – no, Fawkes is the fall Guy in both the seasonal and plot-relevant senses. Good solid popular historian Antonia Fraser tells the central tale, with the odd logical leap, in her 1996 Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot. (Shown here: A stylized image of Robert Catesby printed in C. Northcote Parkinson, Gunpowder, Treason and Plot)

The plotters had a legitimate gripe against the government for its exclusion and fining of Catholics – an Elizabethan policy that the new King James I was mostly choosing not to ameliorate. Alice Hogge’s God’s Secret Agents: Queen Elizabeth’s Forbidden Priests and the Hatching of the Gunpowder Plot describes the long backstory that built Catesby’s grudge.

But then Catesby and Co. truly Intended Treason, as Paul Durst’s title suggests; they wanted to destroy Parliament, with huge loss of life. They wanted the king and queen and their sons dead and a new government with a kidnapped princess as figurehead. Given the era, it’s hard to blame the government for reacting with some particularly unpleasant torturing and executing. G.B. Harrison’s A Jacobean Journal, compiled from documents, publications, and correspondence of the time, captures how the country took it personally: “Very early this morning a most horrible conspiracy of the Papists against the King and the whole realm was discovered...It is not as yet known how far this treason may extend, though it is well perceived to be practised and commenced by some discontented papists; and everywhere there is a general jealousy. The common people mutter and imagine many things, and the nobles know not whom to clear or whom to suspect.”

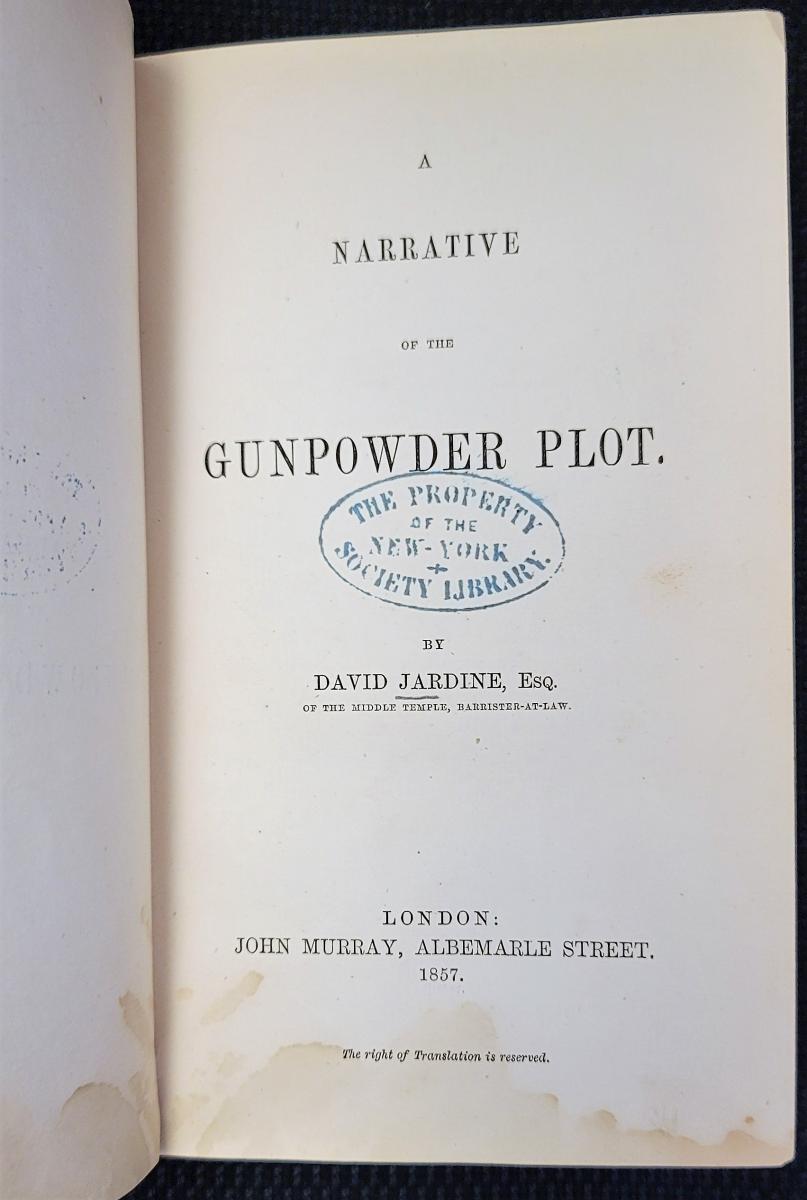

But then the king and his Secretary of State – Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury – also weren’t letting a good crisis go to waste, and it was child's play to tar their enemies list with presumed pitch of plot foreknowledge. At least one man barely connected to the plotters went to the scaffold, and some panicked abridgment of civil liberties took place. The slim volume What Gunpowder Plot Was, by Samuel Rawson Gardiner, dynamites an earlier book that claimed the whole thing was Salisbury’s concoction to beat down the Catholics. (Shown here: the Plot remembered in 1857, reconstructed by David Jardine, and in 1882, Memoirs of the Court of King James the First by Lucy Aikin.)

But then the king who wrote humanely that "I will never allow in my conscience that the blood of any man shall be shed for diversity of opinions in religion” largely refrained from igniting a wildfire of anti-Catholic mood in his two countries. By the lights of the times, and the standards of his predecessors, the response was fairly contained...

...which is striking because, bizarrely, this was the second gunpowdered crisis in James’ life. His own father, consort of Mary, Queen of Scots, had died in an explosive conflagration in February 1567. Neither plot went as planned - Lord Darnley actually escaped the house fire to be strangled just outside – but you can see where the king may have felt he was born on a powder keg. (A vast assortment of fiction, nonfiction, and scandalmongering related to Mary, Queen of Scots here.)

Shakespeare’s tragedy of the Thane of Cawdor, king hereafter, was certainly conceived in part to reference King James’ Scottish forebears. It was also sparked by the Gunpowder Plot, as Garry Wills’ detailed comparison of the play’s language to language about the plot proved to me. I found his Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare’s Macbeth a satisfying reclamation of the often problematic “Scottish Play.”

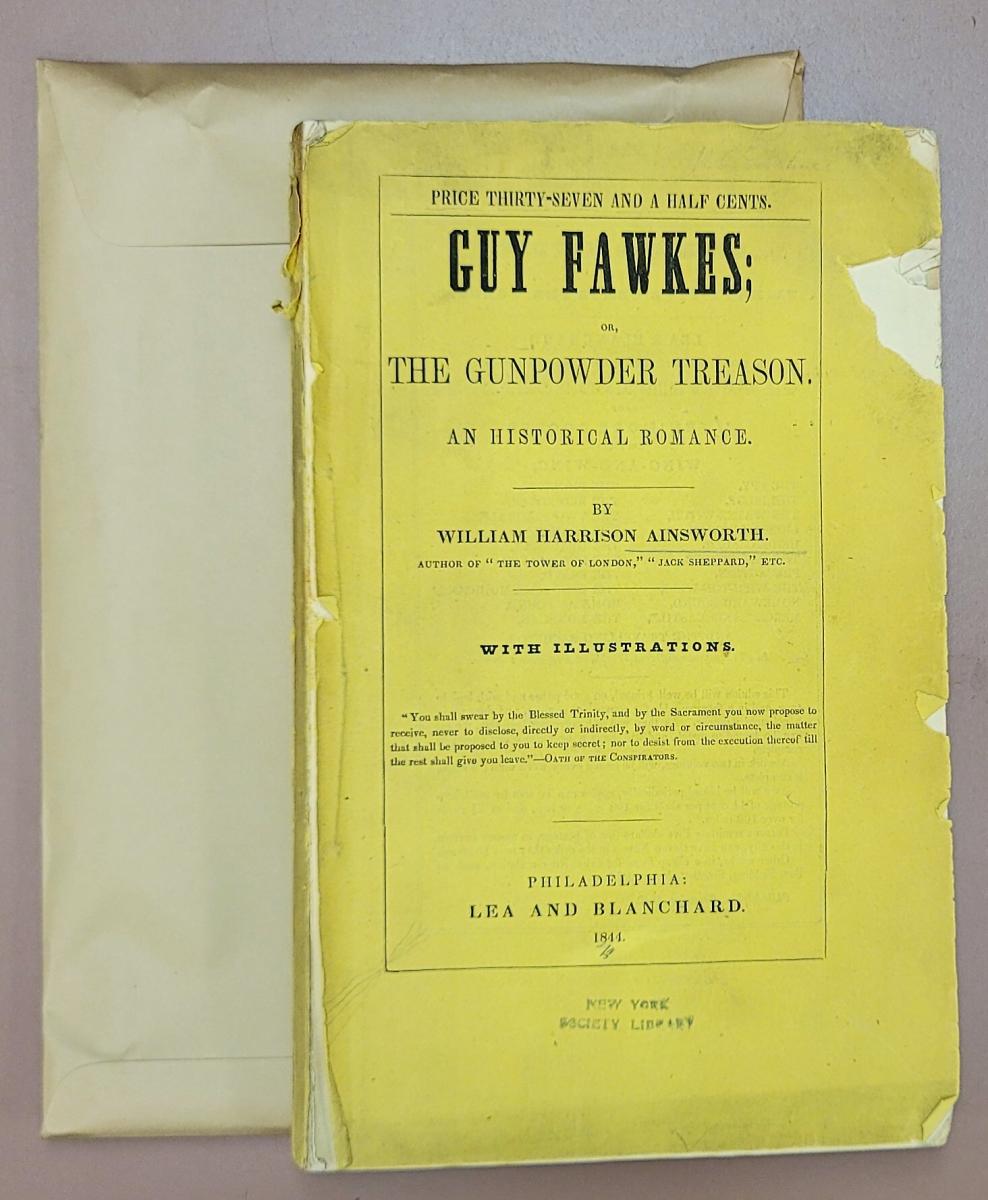

The Library holds surprisingly little Gunpowder-related fiction, but I did have the pleasure of briefly viewing a paperback of William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1841 Guy Fawkes: or, The Gunpowder Treason: an Historical Romance, an potboiler of dastardly deeds and derring-do that resurrects Fawkes as a populist hero. Tracy Borman’s historical series also covers the moment with her 2018 The King’s Witch: A Novel.

Substantial mentions of the Plot and its times appear in Margarette Lincoln’s London and the 17th Century: The Making of the World’s Greatest City, Philip Caraman’s The Years of Siege: Catholic Life from James I to Cromwell, and many of the books about the reign of James I in England generally.

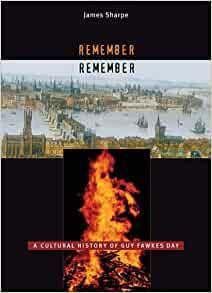

I’m guided in all this by James Sharpe’s brisk, readable, and concise Remember, Remember: A Cultural History of Guy Fawkes Day, from 2005.

Thanks for joining me on this visit to the Westminster cellars, by way of the Library's stacks.

Disqus Comments