Reading the Suffragists! Part I

Since January 30, 2019, suffragists captured in 19th-century portraits have been gazing down on visitors to the Peluso Family Exhibition Gallery. Their collective gaze was unavoidable, persistent, and even noble as they perched above the exhibition cases during the run of Women Get the Vote: A Historic Look at the Nineteenth Amendment. Dominating the gallery for the next eight months were some of the most brilliant and consequential women and men of the suffrage movement, from Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Susan B. Anthony and William Lloyd Garrison. Theirs was a crusade that began in 1848 (although there was much activity before then) at the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, and ended in 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land. (The women’s movement goes on furiously today with unfinished work still ahead.) Then, the Friday before Labor Day, the exhibition finally came down. With the signage peeled off the walls, the backing of sticky bands of blue tape leaving faint traces, it seemed as if the suffragists and their cause had vanished from the gallery. All that was left to do was to remove the books from the cases.

The books were the hardest to return to the stacks. In the months before the opening, co-curator Cathy McGowan and I spent many hours scanning the Library’s collection. We explored the online catalog for Suffrage--United States, Women Suffrage--New York State, Suffragists--England, Suffragists--North Carolina--Biography, and so on. Then, leaving the flat landscape of the digital catalog, we headed to the physical world of books in the closed stacks collection and Stack 7, the Library’s biography collection. Then we separated to pursue our own pathways in other stacks. In the Marshall Room I read a 1792 copy of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a treatise read by early suffragists, from the Special Collections. One by one we found the books, or maybe the books found us. In the end we looked at or read more than a hundred about the suffragists and their crusade. I had my favorites and Cathy had hers. (Cathy’s post about her favorite suffrage books follows mine.)

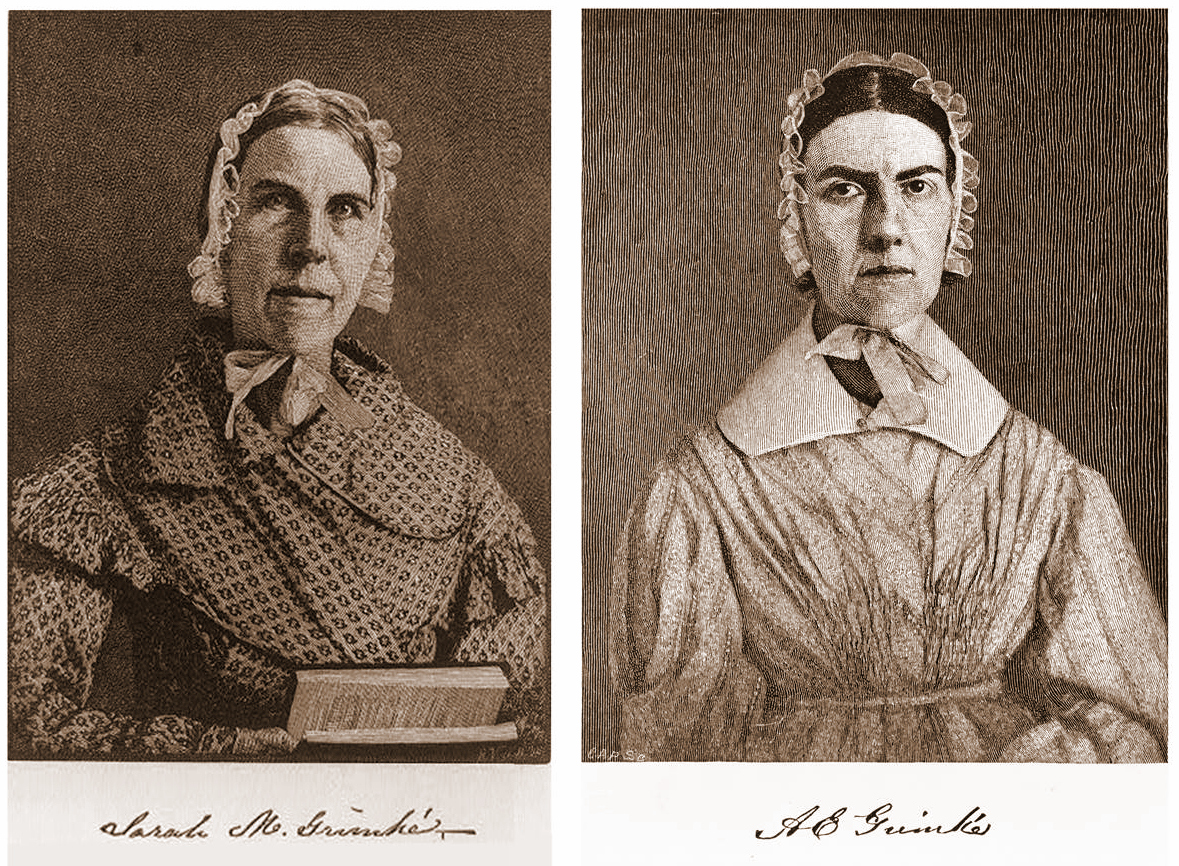

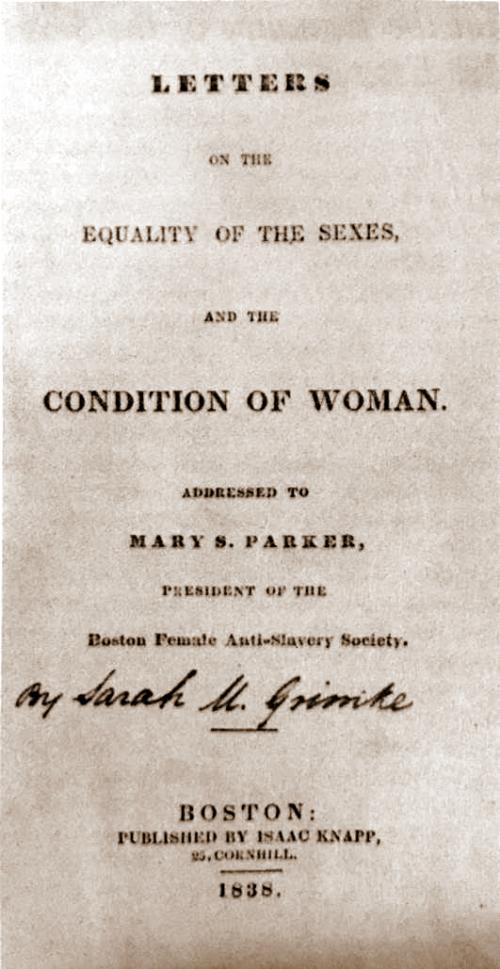

I never took any of the books home. It was my one rule, for I likened each one to a suffragist I might leave on the subway. In time I chased down three remarkable titles. In Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States, Eleanor Flexner writes about Sarah and Angelina Grimké, both brilliant advocates of abolition and women’s rights. As Flexner observes, they loathed “slavery and all its works. Nor could they close their eyes and live with it.…for years they sought painfully for the way to strike a blow against the institution they abhorred.” In The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina, Rebels Against Slavery, another compelling book, Gerda Lerner describes how as a little girl Sarah had tried to run away from home to find a place where there was no slavery. For Angelina, slavery was equally unbearable. Inspired by Sarah’s flight north, Angelina joined her sister in Philadelphia, both living for a time with the Quakers. By the 1830s, the Grimkés were agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society, lecturing in more than sixty towns throughout New England. On Slavery and Abolitionism contains a collection of their speeches, including Sarah’s 1836 Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman. The epistle refutes the belief that God had reserved a special “domestic sphere” for females. Then there is Angelina’s passionate February 21, 1838 Address to the Massachusetts Legislature, which resonates today. “I stand before you as a southerner, exiled from the land of my birth by the sound of the lash, and the piteous cry of the slave….I stand before you as a moral being…and as a moral being I feel that I owe it to the suffering slave, and to the deluded master, to my country and the world, to do all that I can to overturn a system of complicated crimes, built up upon the broken hearts and prostrate bodies of my countrymen in chains, and cemented by the blood and sweat and tears of my sisters in bonds.” Angelina’s speech electrified the nation and set in motion the election of Abraham Lincoln two decades later. According to historian Mark Perry, the Grimkés’ epistles are part of the foundation of our republic.

There is more to say about the Grimkés. In 1838 Angelina married the abolitionist Theodore Weld, and except for one brief period Sarah Grimké remained part of the Weld household. There was another matter of lasting imortance to the entire family. In 1868, reading an article in The National Anti-Slavery Standard, Angelina noted the names of Archibald and Francis Grimké. Although the family name was theirs, she had no knowledge of the boys. They were, she discovered, the children of her brother Henry and Nancy Weston, who had been his slave. Both boys were warmly welcomed into the Grimke/Weld world and in time became crusaders for the causes their aunts had dedicated their lives to. I was eager to read more about them (there are several books about the Grimké family in our collection), but the exhibition deadline was approaching.

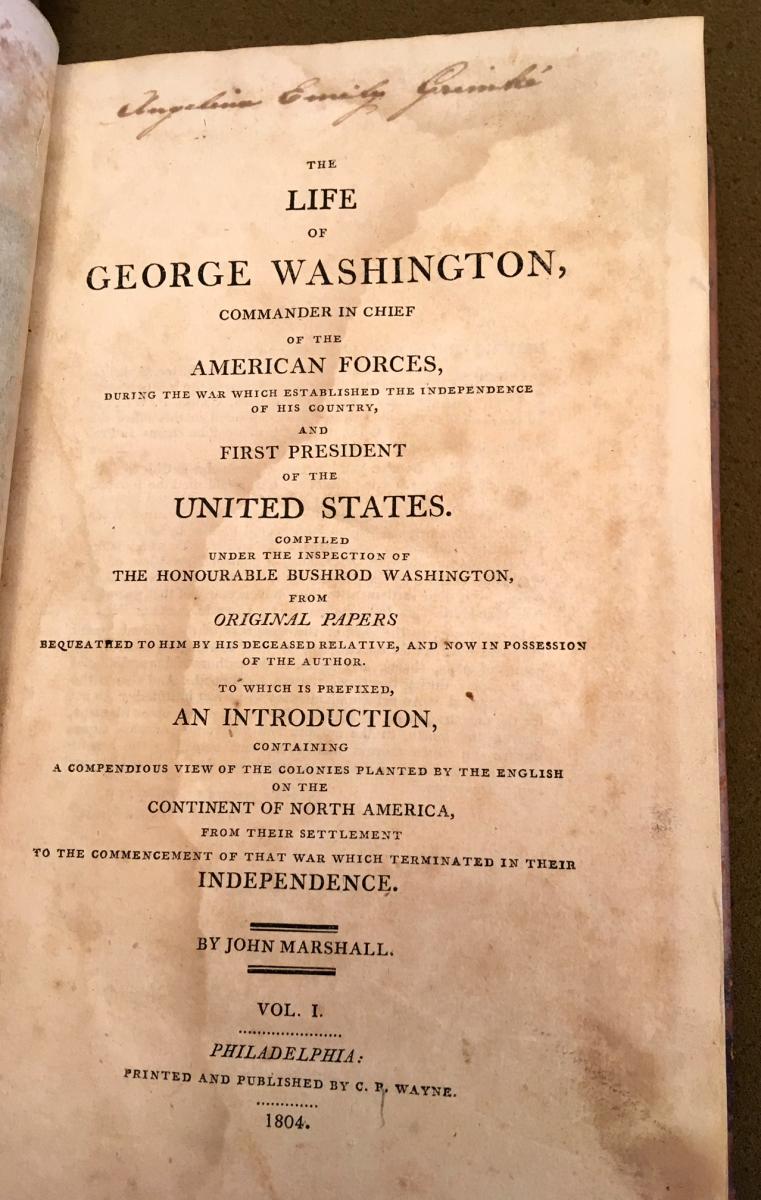

Still there was another record in the catalog that I needed to pursue. Only a few days before the opening, the Special Collections Librarian carried into the reading room - as if a catafalque atop a red book cart - The Life of George Washington, published between 1804 and 1807. There at the top of the title page, I saw the name Angelina Emily Grimké. The signature in black ink was as fresh as if written yesterday. The five volumes of The Life of George Washington that once belonged to Angelina Grimké are now part of the Library’s history.

Disqus Comments