The Eighteenth-Century Society Library

by Nina Root Copyright © 2010

Library member Nina Root is the Director Emerita of the America Museum of Natural History, Research Library, and a confirmed New Yorker.

In 1789 New York City was still recovering from the British occupation during the Revolutionary War; the city had sustained explosions and fires. In 1776 a quarter of the city, including Trinity Church and Broadway, was destroyed by a major fire. The British forces and Loyalists finally departed on November 25th, 1783, and the same day General Washington reclaimed New York, addressing his troops in a farewell speech at Fraunces Tavern. The city was described as "a most dirty, desolate, and wretched place," but returning New Yorkers, then as now, were unbowed and set about rebuilding the physical, commercial, and social city. Washington was inaugurated President on April 30th, 1789 on the porch of Federal Hall (1 Wall Street), the remodeled City Hall. The French-American Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant added a Doric portico to the 1701 building, making it a suitable site for the temporary capital. Slowly the city was reconstructed: a grid system was instituted; banks were established; streets were paved; docks were rebuilt; commerce returned with merchants who had departed; learned and professional societies were organized; and young dandies and belles attended inaugural routs. The city was turning into a thriving metropolis.

The New York Society Library had suspended operation during the years of British occupation, and the collection had been dispersed. Federal Hall again served as the home for the Library, and the entire legislature, as well as the paying subscribers, had use of the collection. Late 18th-century NYSL members were the generation of patriots who declared independence, fought in the Revolutionary War, wrote the Constitution, and rebuilt and revitalized the city. This is the generation that grew up and was educated during the Enlightenment that began in European salons, but whose ideas were fulfilled in the founding of the United States and elegantly expressed in the Declaration of Independence. It is, therefore, fascinating to peruse the charging ledger for 1789-1792 and see what the founding Fathers and the returning veterans were reading and whether patterns can be discerned.

NYSL members were the leading citizens of New York: the lawyers, merchants, physicians, clergy, and socially prominent women. The names are still inscribed in street and place names: Broome, Bowne, Allen, Bleecker, Varick, Kip, Randall, Hamilton, Houston, Jones, Livingston, Clinton, Van Wyck, and Schermerhorn. The Library membership personifies the democratic precepts espoused by the country's founders: fifteen women and at least three prominent Jewish New Yorkers are included in the first roster of dues payers.

Selected by the Library trustees from catalogs and lists, the collection is a typical 18th-century library including the classics (Aristophanes, Cicero, Cato, Ovid, Virgil, Milton, and Shakespeare), histories (Gibbon) and biographies, encyclopedias (Encyclopaedia Britannica) and dictionaries (Johnson), with a good smattering of military history, the Revolution, the latest literature, poetry, and plays (Beaumont and Fletcher, Chesterfield, Congreve, Pope), and the latest novels such as Le Sage's Gil Blas of Santillane and Samuel Richardson's Pamela and Clarissa. Sciences, nature, farming, gardening, economics (Adam Smith), and mathematics were included along with Franklin's Experiments and observations on electricity. Some texts on religion were also to be found. A sizable number of sentimental, romantic novels were included and borrowed frequently by gentlemen; some sound absolutely lurid, reminiscent of the Barbara Cartland variety. The titles are descriptive: The Fortunate country maid; Love and madness, a story too true; History of the fair adultress. These stories were the vogue and were read by everyone, including the clergy.

Among the historical material being read were books on the Ottoman Empire, Islam, the life of Muhammad, and North Africa. The young nation was being harassed by Barbary pirates; American ships were being captured and the crew and passengers held for ransom. Congress even appropriated funds to pay the ransoms. When the U.S. was a colony, the British Navy had protected American ships, and the French fleet protected our interests until the United States was formed. Now U.S. shipping was being intercepted by the pirates. Thomas Jefferson, U.S. envoy to Paris, who opposed paying ransom, went to London to negotiate with the Bey of Morrocco. The Bey explained to Jefferson that the Koran required that infidels be enslaved, and quoted a passage from the Koran. Jefferson, a Deist, unfamiliar with the precepts of Islam, was taken aback. Jefferson bought a copy of the Koran (now in the Library of Congress), and perhaps sent a copy to John Jay. The young country was concerned and was preparing for its first foreign war. In reporting to Jay, then Foreign Secretary of the Continental Congress, Jefferson sent the Bey's Koranic quote:

"The Ambassador (Ambassador Abdrahaman) answered us that it was founded on the Laws of their Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that all nations who should not have acknowledged their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as Prisoners, and that every Musselman who should be slain in battle was sure to go to Paradise."

The great age of exploration began in the 18th century, and many elegant, illustrated reports were published. Books on travel and exploration were popular, especially Cook's multi-volume work. Cook's voyages were among the first to be accompanied by a naturalist and an artist. The folios are illustrated with engravings and with detailed description of the inhabitants of distant islands and the flora and fauna. The voyages of Anson, Bruce, Forster, and Sparrman were read with equal interest.

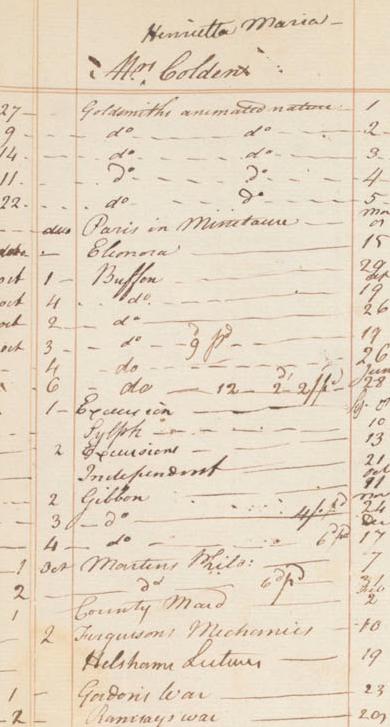

Women members read a lot more than the latest sentimental novels. Notably, Henrietta Maria Colden had very wide reading interests. As an intimate of the Hamiltons and Burrs, she was a welcome addition at dinner parties. Aaron Burr also borrowed books on a wide variety of topics, and his brilliant daughter, Theodosia, may well have read the same volumes and perhaps discussed them with Mrs. Colden. Abigail Adams, known for her intelligence, was in residence during this period, but neither she nor her husband borrowed the latest literature.

Benjamin S. Judah, one of the Jewish members, borrowed a number of plays. His son, Samuel B.H. Judah (ca.1799-1876) , became a successful playwright until he wrote Gotham and the Gothamites (1823), for which he was indicted for libel and imprisoned.

Benjamin Seixas, a Revolutionary War veteran and avid reader, was the great grand uncle of Arthur Hays Sulzberger, publisher of The New York Times from 1935 to 1961.

A few books are of interest to mention. The History of Women by William Alexander (1779, two volumes) was borrowed by a significant number of men, but not by a single woman. The advertisement states: "AS the following Work was composed solely for the amusement and instruction of the Fair Sex; and as their education is in general less extensive than that of the men; in order to render it the more intelligible, we have studied the utmost plainness and simplicity of language; have not only totally excluded almost every word that is not English, but even, as much as possible, avoided every technical term." Enlightenment gentlemen seem to have been as perplexed by the fairer sex as are the men of today. An essay on brewing by Michael Combrune was borrowed a few times by only one NYSL member, Alexander Robertson, a merchant and elder of a church. A little moonshine or sacramental wine? And then there's Essay on the art of ingeniously tormenting, with proper rules for the exercise of that pleasant art by Jane Collier, 1757. This was a bestseller read by a goodly number of members, including Reverend William Linn, chaplain to the Congress, and the indomitable Henrietta Maria Colden.

So, here we have a picture of the reading habits of 18th century members. I suspect that a review of today's borrowers would produce a similar portrait.