Talking Books: Conversations from History by Heidi K. Weber

In a prior NYSL book recommendation post about The Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces, I noted that the exhibit curator Adam Eaker characterized the show as a "conversation." Eaker’s comment got me thinking about conversation and books. Looking back at various eras in history through the lens of several books in the Society Library’s collection may help us imagine what has been said and left unsaid, to "hear" some conversations that shaped lives, ideas, and creative endeavors.

Conversation Before a Revolution: Salons For a Better Society or Just Social Palaver?

The traditional historical narrative gives Catherine de Vivonne, Marquise de Rambouillet, credit for organizing the first salon. It was likely a literary event, probably akin to a book club.

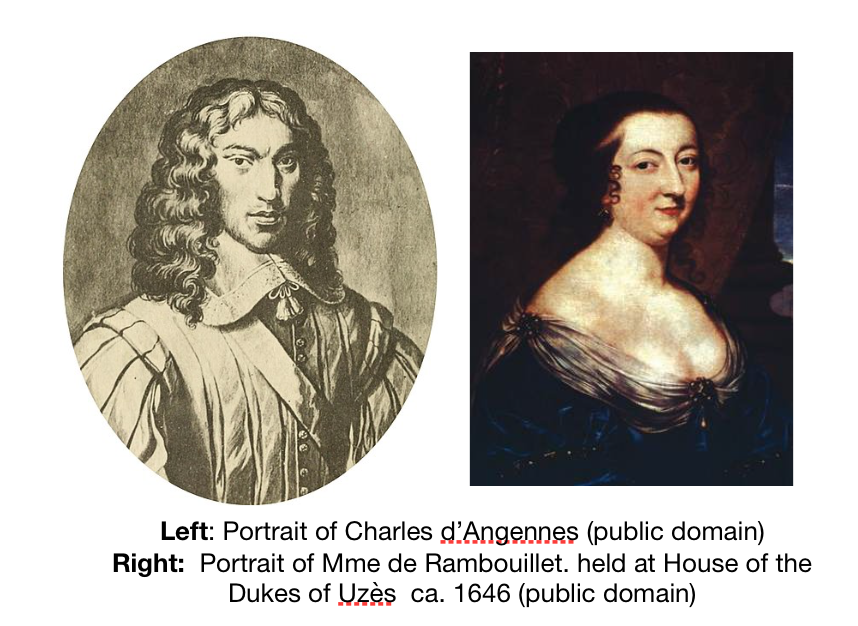

Born in Rome to Italian nobility in 1588, Catherine was married off at age 12 to Charles d’Angennes, who was 23. Charles would become Marquis de Rambouillet a few years later. Sometime around 1618, now a society maven, Madame de Rambouillet, leery of the gossipy, sometimes dangerous discourse of the French royal court and sensitive to the mud and stench of the Paris streets, decided to create an alternative space for gatherings. After taking charge of a massive architectural renovation in her grand home situated between the Louvre and Tuileries Palace, she invited a curated group of friends to visit. Her gatherings were a huge success and set a blueprint for future hostesses.

Benedetta Craveri, an Italian scholar of French 17th-18th-century history, explores the world of the salon in her fascinating book The Age of Conversation (2001 Italian / 2005 English translation). Craveri has done conventional academic research, and her elegant, brocaded prose often mirrors the world she profiles. Her copious footnotes and nearly 100 pages of endnotes attest to her rigorous scholarship. The world Bernadetta Craveri presented of the French Salon matched the notions I pieced together from history class and movies like Dangerous Liaisons, and I was content with the image of salons I had in my head until I had a conversation with another book.

Benedetta Craveri, an Italian scholar of French 17th-18th-century history, explores the world of the salon in her fascinating book The Age of Conversation (2001 Italian / 2005 English translation). Craveri has done conventional academic research, and her elegant, brocaded prose often mirrors the world she profiles. Her copious footnotes and nearly 100 pages of endnotes attest to her rigorous scholarship. The world Bernadetta Craveri presented of the French Salon matched the notions I pieced together from history class and movies like Dangerous Liaisons, and I was content with the image of salons I had in my head until I had a conversation with another book.

A few years after Craveri wrote her book, Antoine Lilti, a young French scholar, professor, and cultural historian, produced a new conversation about French Salons. His book The World of the Salons: Sociability and Worldliness in 18th Century Paris (2005 French, 2015 English translation), generated much debate within the Academy and received much praise. He is now regarded as a star in the field.

Lilti argues salons were less a hotbed of political activism and more for the rich and powerful — or those that wanted to be. No one else's bank account could handle the cost. Lilte writes, "Hospitality came at a price that was not within everyone’s reach. It was not enough to be witty and have friends in order to create a salon.” Hosting a salon required a home able to comfortably seat up to 30-50 guests, a table with provisions for a sumptuous meal, a variety of entertainments, a staff to manage the carriages, prepare the gastronomic extravaganzas, serve the guests, then clean up the mess until the next salon — often the following week. Given these parameters, Lilte argues that salons were spheres that perpetuated and supported the ideas, mores, social structures, and conversations of the wealthy, urban elite. His depiction of the salon departs from Craveri's more traditional notions.

account could handle the cost. Lilte writes, "Hospitality came at a price that was not within everyone’s reach. It was not enough to be witty and have friends in order to create a salon.” Hosting a salon required a home able to comfortably seat up to 30-50 guests, a table with provisions for a sumptuous meal, a variety of entertainments, a staff to manage the carriages, prepare the gastronomic extravaganzas, serve the guests, then clean up the mess until the next salon — often the following week. Given these parameters, Lilte argues that salons were spheres that perpetuated and supported the ideas, mores, social structures, and conversations of the wealthy, urban elite. His depiction of the salon departs from Craveri's more traditional notions.

If you are looking for fiction that captures conversation from the age of salons, you might consider a novel by the late New York lawyer turned novelist (and longtime Society Library member and trustee) Louis Auchincloss. Frequently compared to Henry James and Edith Wharton, Auchincloss often wrote novels centered on the world of privilege and power. His historical novel The Cat and The King (1981) is a mix of fact and fiction about the court of French King Louis XIV (1638–1715). The book’s narrator is based upon a real French aristocrat, Louis de Rouvroy, the second Duc de Saint-Simon. In this fictional memoir, an imagined de Rouvroy records his observations and the intrigues of life at the court of the Sun King. There is also Antonia Fraser’s Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King (2007). This biography of Louis and his many women — from his mother, his queen, his mistresses, and courtesans — makes the Kardashians look simply banal.

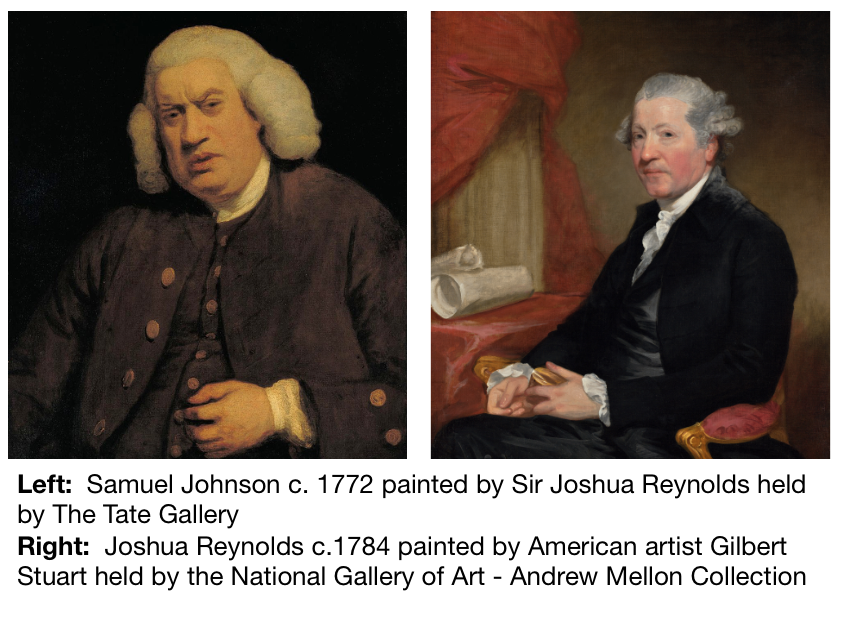

Conversation as a Club for Well-Being: Samuel Johnson and Friends

While the French were having their say in salons, there was another conversation fermenting across the channel.

In the winter of 1763-64, a small group of friends was invited to gather in London. All shared a concern for the well-being of one of their brethren, Samuel Johnson. Johnson  had lost a wife and been forced to move from a large, comfortable home because of severe financial difficulty, and he was searching for his next professional project. His last, compiling the influential and authoritative The Dictionary of the English Language (1755), had been an ambitious and successful venture taking years to complete. Prone to depression and ‘dark moods,’ Johnson now fell into decline.

had lost a wife and been forced to move from a large, comfortable home because of severe financial difficulty, and he was searching for his next professional project. His last, compiling the influential and authoritative The Dictionary of the English Language (1755), had been an ambitious and successful venture taking years to complete. Prone to depression and ‘dark moods,’ Johnson now fell into decline.

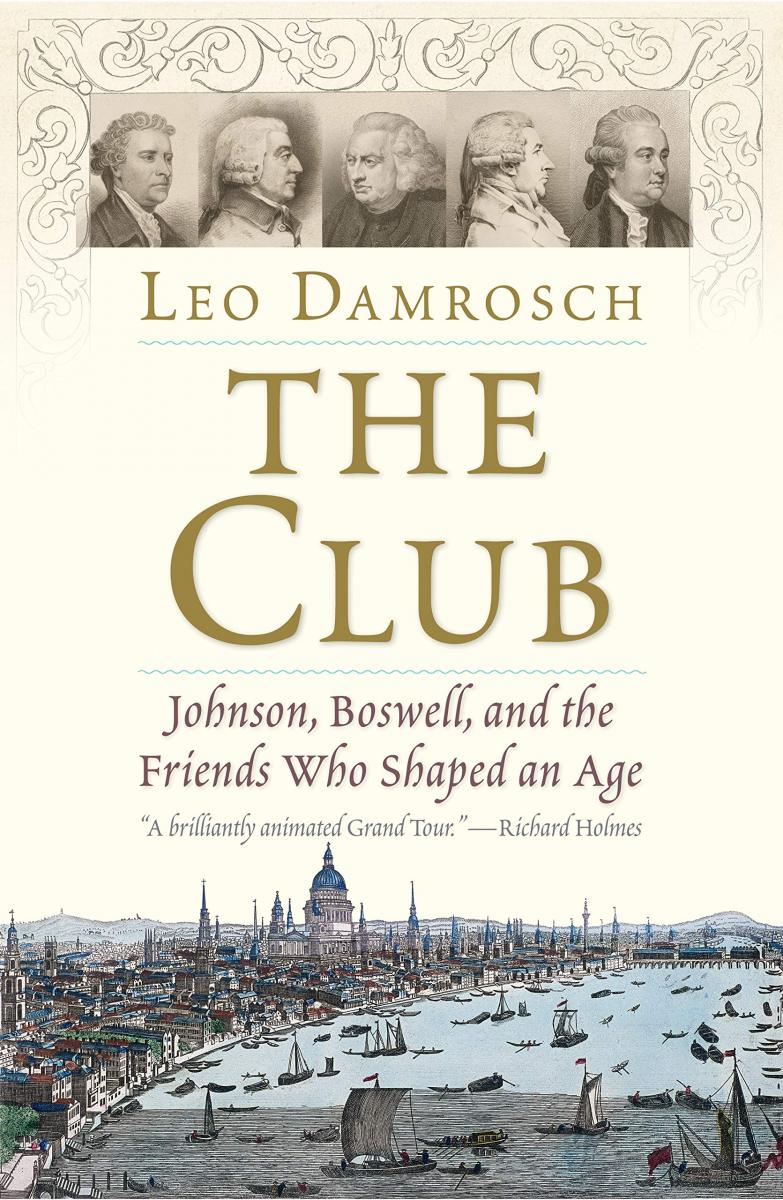

It was agreed that the group of friends, which included Edward Gibbon, Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, Joshua Reynolds, and David Garrick, would gather at the Turk's Head Tavern on Gerrard Street in Soho for libations and conversations. The group eventually became known as The Literary Club or simply, The Club. In The Club: Johnson,  Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (2019), author Leo Damrosch marvelously captures the group’s history and the varied personalities behind it. Damrosch chronicles the idea as it was hatched by the portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. In an era without antidepressants, Reynolds, concerned for Johnson, was forced to rely upon other remedies to improve his friend’s mood. Conversation with learned and interesting men, he thought, might be the ticket to improved well-being. Reynolds was correct. Johnson’s mood improved. Today, wellness and health science experts now encourage conversation and community as part of a cure for "dark moods."

Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (2019), author Leo Damrosch marvelously captures the group’s history and the varied personalities behind it. Damrosch chronicles the idea as it was hatched by the portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. In an era without antidepressants, Reynolds, concerned for Johnson, was forced to rely upon other remedies to improve his friend’s mood. Conversation with learned and interesting men, he thought, might be the ticket to improved well-being. Reynolds was correct. Johnson’s mood improved. Today, wellness and health science experts now encourage conversation and community as part of a cure for "dark moods."

(In October 2020, The Atheneum Library in Philadelphia presented an event with author Leo Damrosch that was shared with the NYSL. Watch a recording here.)

Conversation for Creativity: The Shape of Bloomsbury and Missed Conversations

Dorothy Parker, the writer, critic, and satirist, is said to have quipped that the Bloomsbury Group "lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles." There’s no question that the members of the Bloomsbury Group came in many shapes. Named for the London neighborhood, the Bloomsbury Group was a fluid coterie of largely upper-crust intellectuals, artists, activists, writers, and philosophers.

With a range of interests, the group shared a belief in the importance of art, ideas, and conversation. It was a stunning array of personalities, preferences, and thinkers. When they began to gather, most had yet to create the great works we still appreciate today. One might ask, how much did conversation in these gatherings contribute to the achievements that were to come?

Each member of the Bloomsbury Group has been worthy of at least one biography and/or memoir, and the Library has many. In 2018, NYSL Head of Events Sara Holliday wrote in a blog post:

"Get a room of your own and delve into the Bloomsbury Group’s London: 55 books on the general topic here [now 62 books—ed.]. Virginia Woolf is largely found in Stacks 6 and 9, with Vanessa Bell in 7 and 12. (And did you know you can find Woolf's reviews in the digital Times Literary Supplement)? Lytton Strachey is, of course, a window to his own era and earlier ones, and this biography of his wider family talks empire and feminism in particular. If you don't know Lady Ottoline Morrell, visit her with any of these titles or go just for tea with this small treasure.

I would like to draw your attention to two books in particular:

Bloomsbury: A House of Lions by Leon Edel

Out of print but happily available at the NYSL, Edel’s work is a manageable portrait of nine figures from the group. It’s written in a unique style combining traditional biographical information with interpretations from its author. The book focuses on the connected conversations between the group members as they met and became friends, adversaries, advocates, confidants, and lovers.

The Bloomsbury Group by Frances Spalding

In 2005 the National Portrait Gallery, London put together this beautiful little book. With commentary from art historian, critic, and biographer Frances Spalding, it is a jewel crammed with photographs and images of the group's art along with very brief biographies of 19 of the group’s members. In her introduction, Spalding writes thoughtfully of her subjects,

“Bloomsbury never tired of analyzing their own and other people’s behavior. This testing habit of mind made them very alert, critical of themselves and others. It helped develop a blend of sensibility and intelligence that is particular to these friends — the warming of intelligence by sensibility and the testing of feeling by means of the intelligence. In 1925, on a rare occasion when Virginia Woolf did comment on the group as a whole, she praised her Bloomsbury friends for ‘having worked out a view of life which was not by any means corrupt or sinister or merely intellectual; rather ascetic and austere indeed; which still holds and keeps them dining together and staying together, after twenty years, and no amount of quarreling or success, or failure has altered this. Now I do think this,’ she concludes, ‘rather creditable.’"

It must have been the good conversations.

The Bloomsbury Group has inspired hundreds of pages of fiction. Two recent titles worth a read are the Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Hours (1998) by Michael Cunningham, made into an Academy Award-winning film, and the more recent bestseller Vanessa and Her Sister (2014) by Priya Parmar. Both are inventive re-imaginings of Bloomsbury conversations.

A Missed Conversation

In recent years, with more written about Bloomsbury and the group’s offspring, it has become apparent that some conversations should have happened but didn't.

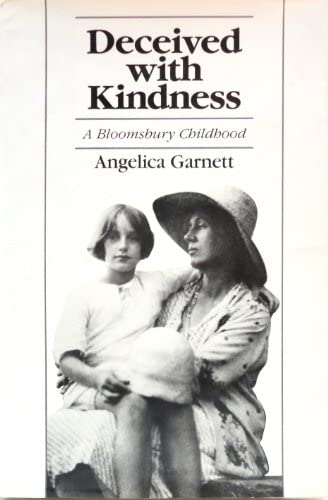

For instance, Angelica Bell Garnett’s revelatory memoir, Deceived with Kindness: A Bloomsbury Childhood, which won the J. R. Ackerley Prize for Autobiography in 1985, has much to say about family conversation.

Angelica was raised by Clive and Vanessa Bell. It is claimed that, on her 18th birthday, her mother had a conversation with her and shared the family secret: her father was not her father. Her "real" father was her parents' friend Duncan Grant, who often lived among them as part of the household menagerie.

Within a few years, at age 24, Angelica announced she intended to marry David Garnett, also a friend of her parents (and son of the famous translator Constance Garnett). Garnett was almost 50 and a longtime member of the Bloomsbury circle. There was concern over the age difference, but there was also another wrinkle. Years before, David Garnett had been her "real" father's lover.

Her family...well, you can imagine.

The marriage took place, officially lasted 25 years, and spawned three daughters. In her memoir, Angelica indicates she was not aware that her husband had been her father’s lover. But John Maynard Keynes, the eminent economist, British public servant, member of the Bloomsbury Group, and also a former lover of Angelica's biological father, had her to tea before her marriage. During their conversation he suggested, as he put it, "It might not be a very good idea." In an interview given late in life, Angelica admitted she probably wasn’t listening to the Keynes conversation. "I was in love,” she said.

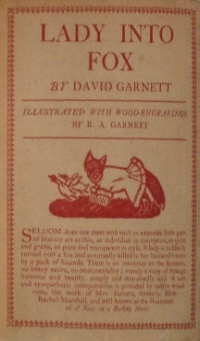

If you’re looking for a short marital fiction that fits oddly and unintentionally well with the above life story, you might consider David Garnett’s novella Lady Into Fox — the story of a man whose wife turns into a fox. The husband and the she-fox have plenty to talk about. Published in 1922, twenty years before his marriage to Angelica, while Garnett was busy running a bookshop with Francis Birrell (with whom it is also said he was romantically involved), the book garnered The James Tait Black Memorial Prize and is a fascinating read with present-day hindsight. (Lady into Fox was previously recommended by Steve McGuirl, NYSL Head of Acquisitions.)

If you’re looking for a short marital fiction that fits oddly and unintentionally well with the above life story, you might consider David Garnett’s novella Lady Into Fox — the story of a man whose wife turns into a fox. The husband and the she-fox have plenty to talk about. Published in 1922, twenty years before his marriage to Angelica, while Garnett was busy running a bookshop with Francis Birrell (with whom it is also said he was romantically involved), the book garnered The James Tait Black Memorial Prize and is a fascinating read with present-day hindsight. (Lady into Fox was previously recommended by Steve McGuirl, NYSL Head of Acquisitions.)

Technology and Talk: The Future of Conversation

I daresay that before the COVID-19 pandemic, most of us took face-to-face conversation for granted. The pandemic put a temporary halt to many of these interactions or transferred them online, thanks to new technology. (If COVID had struck ten years ago, nay, even five years ago, where would we be?) Suddenly, talking online was necessary. It became front-and-center in our personal and professional lives, despite recent cautions from researchers and cultural commentators about the impact of our digital world on meaningful conversations.

In 2015, Dr. Sherry Turkle from MIT argued that our well-being, and the well-being of future generations, was in peril if we didn't get mindful about Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. But Turkle is not a Luddite. She is, in fact, an advocate for technology, although she raised concerns in her book. Relying upon research findings, she argued for a more mindful, sometimes limited engagement with technology if we want good conversation.

In a 2015 New York Times review of Turkle’s book, the writer Jonathan Franzen warned that "Our rapturous submission to digital technology has led to an atrophying of human capacities like empathy and self-reflection, and the time has come to reassert ourselves, behave like adults, and put technology in its place."

A few years before Sherry Turkle’s book, Stephen Miller wrote a lovely book, Conversation: A History of a Declining Art (2006). In a charming series of chapters, Miller outlines the many ways conversation has changed. Miller winds his way from Plato to 18th-century Britain to the America of Ben Franklin and Dale Carnegie. Miller closes his journey with what he sees as the decline of conversation in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, citing theorists like Foucault, egocentric writers such as Norman Mailer, and counterculture icons the Merry Pranksters as examples and harbingers of its decline. In closing, Miller is not sure discourse will survive. He fears that the increasing expression of anger, which he says has become a sign of being a “conscientious citizen,” as well as our modern need to be '”authentic” and speak up, do not always bode well for the exchange of ideas and good conversation.

Miller’s final sentence seems more than a little prescient: “In the United States, where people are admired for being natural, sincere, authentic, and nonjudgmental — for being more like Rousseau than like Hume — the prospects for conversation are not good.“

I, for one, am not ready to give up on good conversation, however. There is so much more to be said.

If you are looking for more conversations at the Society Library, you might check out the wide range of events at the NYSL, the published volumes of conversations and interviews in the stacks, and dozens of additional book recommendation articles.

Heidi K. Weber writes about books on her email newsletter at TheLiterarySalon.com. She also leads webinars and workshops that bring books alive in your personal and professional life.