Book Selections of Founding Fathers

William J. Dean (2007)

William J. Dean is executive director of Volunteers of Legal Service. He serves as a trustee of the New York Society Library.

This article is reprinted with the permission of the New York Law Journal, where it first appeared on Feb. 8, 2007.

On April 30, 1789, from the balcony of Federal Hall, George Washington took the oath of office as President of the United States. The president and Congress shared space in Federal Hall with the New York Society Library.

The Library had been founded in 1754 by a group of six young New Yorkers—five lawyers and a merchant—in the belief that "a Publick Library would be very useful, as well as ornamental to this City..." In the view of one founder, New York lacked "a spirit of inquiry among the people. It is indeed so prodigious that in so populous a City...few Gentlemen have any relish for learning. Sensuality has devoured all greatness of soul and scarce one in a thousand is even disposed to talk serious."

Books were ordered from England. They included a Life of Mahomet, the works of Milton and Locke, a history of France ("the best"), lives of Cromwell and Tsar Peter, "All Cicero's Works that are translated," and debates in Parliament.

In October 1754, the books arrived from England on the Captain Miller. With a library, New York now had an opportunity, the New York-Mercury editorialized, to "show that she comes not short of the other Provinces, in Men of excellent Genius who, by cultivating the Talents of Nature, will take off that Reflection cast on us by the neighbouring Colonies, of being an Ignorant People."

From 1774 to 1788, the Library suspended operations. During the Revolutionary War, British soldiers carried away library books in their knapsacks, bartering them for grog. 600 books were removed to St. Paul's Chapel. When the Library re-opened in 1789, it had a collection of 3,100 books.

The Library was available as a resource to its 239 subscribing members, among them Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and John Jay, and to the president, members of Congress and justices of the Supreme Court. Occupying a room on the top floor, the Library was the only institution in Federal Hall not mandated by the U.S. Constitution.

The Library's charging ledger for 1789-92, bound in leather and weighing 18 pounds, was misplaced for years and then found in 1934 in a trash pile in the basement of its fourth home at 109 University Place. (Since 1937, the Library has been in its fifth home at 53 East 79th Street.) Today the ledger is a priceless, but crumbling possession, recording titles of books taken out and the names of borrowers.

June 24, 1789. The first entry in the ledger records that the Reverend Dr. Lynn borrowed Animated Nature by Oliver Goldsmith. Dr. Lynn served as chaplain to the Congress. He was fined seven pence for returning the book late.

July 31. "Elements of Criticism - 1 - Ovo. H. Vice-president-self." Shorthand for Vice-President John Adams himself appearing at the Library to take out volume 1 of Elements of Criticism (octavo size), a philosophical work by Lord Henry Kames. Volume returned on Aug. 17.

Aug. 21. Volume 2 taken out by "Doork" for "H. Vice-President." This time, instead of personally coming to the Library, the vice-president sent the doorkeeper to collect the second volume of Elements of Criticism. No record of volume 2 being returned.

October 5. "Law of Nations [&] Commons Debates - volume 12 - President." Here the ledger records that President Washington took out The Law of Nations by Emmerich de Vattel. Also, volume 12 of the House of Commons Debates. The ledger does not record whether the president came in person or sent a messenger, nor is there any record of either volume being returned, or the president or vice-president being fined.

Alexander Hamilton borrowed two novels, The Amours of Count Palviano and Eleanora and, as recorded in the ledger, "Edward Mortimer (hist. of) by a lady."

In 1789, Aaron Burr took out Revolutions in Geneva; a volume of Swift; and Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Gibbon. In 1790, he turned to Voltaire, reading nine volumes and then to the 44 volumes making up the series, An Unusual History, self-described as a history "from the earliest account of Time, compiled from original authors." His lighter reading included the novels, Mysterious Husband and False Friend.

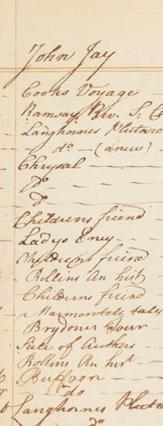

On Feb. 1, 1790, in a building on Broad Street called the Exchange, the U.S. Supreme Court held its first session. The New York Society Library charging ledger records books borrowed by Chief Justice John Jay. These included:

Literature. The works of Jonathan Swift; Don Quixote, Voltaire's, Candidus, or All For the Best, as the volume is noted in the ledger; The Fair Syrian, a novel; Frances Burney's, Cecilia, or Memoirs of an Heiress; Arabian Nights Entertainments, consisting of one thousand and one stories, related by the Sultaness of the Indies and John Aubrey's Miscellanies, a collection of stories on ghosts and dreams.

History. Plutarch's Lives; Lives of the Admirals, and other Eminent British Seamen; The History of the Five Indian Nations of Canada; The History of the Revolution of South Carolina, from a British Province to an Independent State; and An Essay on the Life of the Honorable Major-General Israel Putnam.

Travel. Captain James Cook's A Voyage towards the South Pole, and Round the World; A Tour through Sicily and Malta; Travels into Muscovy, Persia, and Paris of the East-Indies, containing an accurate description of whatever is most remarkable in those countries; A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1766-1769, by the Comte Louis Antoine de Bougainville; A General Description of China, containing the topography of the fifteen provinces which compose this vast empire; Travels in Spain; Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in 1768-1773; and Travels in North America in the Years 1780-1782, by the Marquis Francois Jean de Chastellux.

Science. Comte de Buffon's Natural History; Chambers', Cyclopaedia, or General Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; and Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man.

Chief Justice Jay must have had his own collection of law books, for few of the books borrowed by him from the New York Society Library are law-related. What stands out when examining the Library's charging ledger is both the breadth of his interests and his wide reading in literature, history, travel and science. May we, as lawyers, be encouraged by his example to expand, through reading, our own horizons.