Annotations and Archives in Nineteenth-Century New York

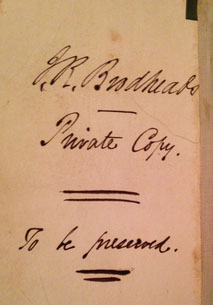

"J.R. Brodhead. Private Copy," reads a note on the opening leaf of The Final Report of John Romeyn Brodhead, one of the books now on display in Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the New York Society Library. Then, emphatically underlined, the insistent direction, "To Be Preserved."

John Romeyn Brodhead's The Final Report is by no means a rare book as far as nineteenth-century imprints go. It was printed in Albany in 1845, and you can even find it these days on Google Books. But the Library's copy is unique because it was the historian's private — and even working — copy. As Brodhead wrote on another endpaper in the same book, there were many errors in the printed version, "some of which I have noted in this copy." He annotated his Final Report extensively, correcting misprints and adding errors to the publisher's "Errata" at the back of the book (p. 375). Brodhead read with pen in hand, as an editor of his own work and as a researcher into early American history. Yet his reading and annotating habits also provide insight into how a historian navigated complex and sometimes poorly cataloged archives in the nineteenth century. What Brodhead learned from his archival adventures about the difficulties and frustrating dead-ends of searching for material informed his time as a trustee of the Society Library from 1858-1871, and ultimately accounts for his books' presence in the Library's collection.

Brodhead was a historian of Dutch New Netherland at a time when America's colonial origins (and subsequent identity) were the subject of much debate. The New-York Historical Society, founded in 1804 in part to counter the pervaisive mythos of the New England Puritan, urged the State to fund the compilation and preservation of the papers that document its history from the seventeenth century onward. The State of New York appointed Brodhead to carry out the task, and he traveled to British and Dutch archives as an Agent of the State government. He returned successfully, with a staggering eighty volumes of transcipts, some of which survive today at the Society Library. In a bid to secure the funds to translate and publish these documents and write a history of New York, he wrote The Final Report, which listed all of the documents he discovered by repository in chronological order. The book acted as a guide to future historians, saving them precious time and resources by documenting the contents of European archival collections at a time when such information would have been tremendously difficult to obtain. But Brodhead never realized his goal of publishing his transcriptions. Instead, in 1849, a state legislature dominated by Whigs appointed two other men to work through the Democrat Brodhead's transcriptions. Nonetheless, Brodhead's labor in European archives was much appreciated, even by his rival editors. Their Documents Relative to the Colonial History of New York says clearly that they were "procured" by Brodhead.

Brodhead's effort to transcribe so many documents highlights the difficulties a historian encountered in locating and navigating sources. A historian like Brodhead often accessed archival documents stored in faraway libraries through printed copies of original manuscripts, sometimes in translation, and often in multiple editions. In Brodhead's Notes on the Albany Records, January 1841, he observed that "[t]he Dutch records in the office (commencing with the year 1638) have been translated" in 1805 and 1818 (p. 4). His annotations suggest that he took a modern printed edition with him to the archive, and noted discrepencies between the reprint and the original. His copy of the Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propogation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts compares page numbers and details between his 1853 copy and the original 1728 text. He noted where "in [the] original edition there is 'a map of the most improved part of Carolina' & 'A map of the province of Carolina, divided with its Parishes &c, according to the latest accounts, 1730, by H. Moll, geographer.'" (p. 36) He also recorded important details about the afterlives of his seventeenth- or eighteenth-century subjects, such as Elias Neau (d. 1722), whose tombstone, Brodhead noted, "has been recently recut by the care of his descendent, Mrs. Oliver K. Perry" (p. 94). As a reader, Brodhead was critical, correcting mistakes (for example, "This is a mistake: Barclay was the author" on p. 72) and resolving disputes, as we see in his copy of Thomas Hutchinson's History of Massachusetts-Bay, also on display. While other historians might dispute the colony's borders, he confidently wrote that "the western limit was the line of the Narreganset [Narragansett Tribe] Country," and even drew a miniature map of the Merrimack River Valley.

Brodhead's annotations and additions to books show that he was constantly seeking new material, combing through newspaper articles and library catalogs to do so. At the back of his  Final Report, he tucked in a newspaper clipping with a review of John Lothrop Motley's Rise of the Dutch Republic (1856), perhaps as a reminder for further reading. His notes on papers relating to Leisler's Rebellion (1689-1691), an uprising in New York against English colonial rule, show just how Brodhead tracked down older documents. Next to his listing of Jacob Leisler's Narratives of the Grievances and Oppressions, which the inhabitants of New York lie under (1690) in the Final Report, Brodhead wrote "This is a quarto pamphlet of 26 pages in the British Museum. shelf mark 1061.g2" (p. 131). The British Museum's collection of books and manuscripts — now in the British Library — inspired Brodhead's highest praise. It was a "magnificent monument"; its collection of printed books was "one of the most perfect in existence" and just as importantly, it was easy enough to consult rare materials. Nonetheless, in an insert to the Final Report titled "Printed papers in the British Museum" Brodhead noted three single sheet printed texts that he could not locate. At the bottom of the sheet he wrote, "See Kings Library. Mr. Panizzi." Anthony Panizzi, keeper of printed books (including those in the King's or Royal Library collection) at the British Museum (and later principal librarian), was also at work on a new catalog for the printed books, which Brodhead praised extensively —a "systematic alphabetical catalogue of such comprehensiveness, that the letter 'A' alone occupies about twenty large folio volumes" (p. 3). While Panizzi is positively remembered for his reforms to the British Museum in acquiring new material and his new catalogue, these were controversial at the time. Brodhead was clearly an early supporter. He hoped that Panizzi would know where to find those elusive documents relating to Leisler's rebellion.

Final Report, he tucked in a newspaper clipping with a review of John Lothrop Motley's Rise of the Dutch Republic (1856), perhaps as a reminder for further reading. His notes on papers relating to Leisler's Rebellion (1689-1691), an uprising in New York against English colonial rule, show just how Brodhead tracked down older documents. Next to his listing of Jacob Leisler's Narratives of the Grievances and Oppressions, which the inhabitants of New York lie under (1690) in the Final Report, Brodhead wrote "This is a quarto pamphlet of 26 pages in the British Museum. shelf mark 1061.g2" (p. 131). The British Museum's collection of books and manuscripts — now in the British Library — inspired Brodhead's highest praise. It was a "magnificent monument"; its collection of printed books was "one of the most perfect in existence" and just as importantly, it was easy enough to consult rare materials. Nonetheless, in an insert to the Final Report titled "Printed papers in the British Museum" Brodhead noted three single sheet printed texts that he could not locate. At the bottom of the sheet he wrote, "See Kings Library. Mr. Panizzi." Anthony Panizzi, keeper of printed books (including those in the King's or Royal Library collection) at the British Museum (and later principal librarian), was also at work on a new catalog for the printed books, which Brodhead praised extensively —a "systematic alphabetical catalogue of such comprehensiveness, that the letter 'A' alone occupies about twenty large folio volumes" (p. 3). While Panizzi is positively remembered for his reforms to the British Museum in acquiring new material and his new catalogue, these were controversial at the time. Brodhead was clearly an early supporter. He hoped that Panizzi would know where to find those elusive documents relating to Leisler's rebellion.

Brodhead's experience in the British Museum and other European libraries changed his conception of how libraries ought to operate. At the British Museum, he wrote, "no where else was I more strongly convinced of the indispensable necessity to the investigator, of accurate catalogues" (p. 3). But he was also impressed by the sheer breadth of the Museum's holdings. As a Trustee of New York Society Library and member of the Library Committee (today's equivalent of the Books Committee, except that Library Committee members often bought books themselves for which they were reimbursed by the Librarian or Treasurer), it is possible that he in the Library's budding desire in the mid-nineteenth century to rival the impressive collections of European libraries, above all that of the British Museum (Keep, 471). Brodhead's desire to imitate the British Museum is all the more interesting when compared to another historian's opposite reaction to Panizzi and his program: Thomas Carlyle was so upset that Panizzi would not afford him special treatment as a reader that in 1841 he founded the subscriptin-based London Library - a library that looks much more like the New York Society Library today. The Society Library's aspiration led to the acquisition of the Hammond Collection and countless other donations, including, after Brodhead's death, the gift of over one thousand of his books, pamphlets, and papers by his widow (Keep, 473). Brodhead's annotated books are an important part of his personal archive, providing a window into changing research methologies and institutional aims. His efforts to preserve his books are in many ways as telling as his annotations themselves.

To learn more about John Romeyn Brodhead and other annotators and books in the Library's collections, visit Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the New York Society Library. The exhibition is on view in the Peluso Family Exhibition Gallery at the Society Library through August 15, 2015.

Disqus Comments