Overlooked Books: Thomas Morton's New English Canaan

You probably have known the story since first grade: four hundred years ago, the Pilgrims sailed on the Mayflower to settle in North America. They endured ten weeks at sea, sickness and cold because they wanted to be able to worship as they pleased without interference from English authorities. After arriving at Plymouth in November 1620, they struggled to survive a terrible winter in Massachusetts. By the fall of the following year, however, they called for a feast to give thanks for the bounty they now enjoyed. Along with Pilgrim families, 90 native Americans attended that first Thanksgiving. The natives were welcome because they had taught the Pilgrims how to hunt and fish, fertilize the soil and grow maize (Indian corn). Without their help during that awful first year, the Pilgrims might not have survived.

The story may seem the stuff of legend, but the diary of famed Pilgrim leader William Bradford validates the details down to a menu that might have included cod and bass, duck, venison, and Indian corn. Oh yes, Bradford famously references a “… great store of wild turkeys.”

In terms of travel, Thanksgiving is our most popular holiday. For parents and teachers it offers a chance to remind youngsters to give thanks for what they have and not just what they hope to get for Christmas. Also we can celebrate a rare moment of friendship between settlers and indigenous people before the coming of their terrible conflicts.

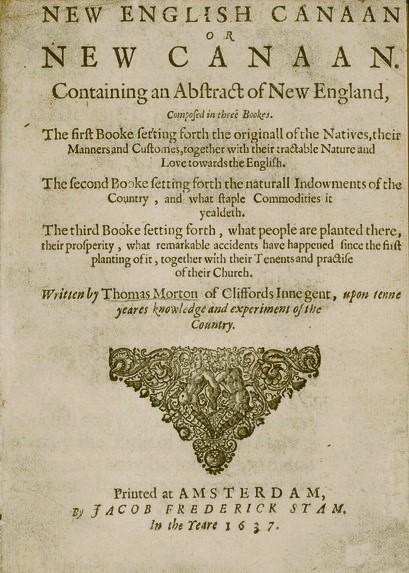

While Bradford’s diary, Of Plymouth Plantation, remains the essential source, there is an overlooked book in the NYSL stacks, Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan, that offers an alternative view, though not perhaps suitable for children.

Three years after the first Thanksgiving, Thomas Morton took control of a nearly defunct settlement about 30 miles north of Plymouth. But if Plymouth stood for piety, then Merrymount meant having a good time where one might also trade with the natives, exchanging wampum and hardware for furs and beaver skins.

The Pilgrims dubbed Morton “the Lord of Misrule” after he invited natives, runaway servants, and strangers to drink, sing, dance, and frolic around an eighty-foot tall maypole which he had festooned with his own verses celebrating the pagan gods. If there was sex between white settlers and native women, then Morton apparently had no objection. Merrymount, after all, was about “harmless mirth made by young men.” More troubling, Morton sold guns to the natives, which not only enhanced their ability to secure beaver skins, but also to attack New England settlements.

The Pilgrims dubbed Morton “the Lord of Misrule” after he invited natives, runaway servants, and strangers to drink, sing, dance, and frolic around an eighty-foot tall maypole which he had festooned with his own verses celebrating the pagan gods. If there was sex between white settlers and native women, then Morton apparently had no objection. Merrymount, after all, was about “harmless mirth made by young men.” More troubling, Morton sold guns to the natives, which not only enhanced their ability to secure beaver skins, but also to attack New England settlements.

In 1628 Pilgrim enforcer Miles Standish, aka “Captaine Shrimp,” arrested Morton, but after being deported, he soon returned – to the Pilgrim’s “terrible amazement.” After two years he was again sent back to England where he conspired with the influential Fernando Gorges, who, through connections to Charles I and Archbishop Laud, sought to wrest control of New England from the Pilgrims and the newly arrived Puritans. While in England Morton found the time to write the New English Canaan (1637) which promoted New England as a land of milk and honey yet also inhabited by fanatical settlers who had separated from the Church of England.

When he first came to New England, Morton explained that he had encountered “… two sorts of people, one Christians, the other infidels… [ who were] …more full of humanity and more friendly than the other.” Because they could hunt, fish and live comfortably off the land, the godless savages were untainted by Christian greed and double-dealing. And even though the Pilgrims themselves may have been victims of intolerance, they all too quickly exiled those who failed to conform to their terrible strictures. Nor did they hesitate to massacre the natives.

Morton often depicts himself less as a victim than as “mine host,” an unabashed provocateur, a role which he found so irresistible that when his plan to conquer New England fell apart, he headed back to Massachusetts Bay, putting himself once again in harm’s way. He seemingly could not resist the temptation to taunt the self-righteous, with the perfect mark being the Pilgrims who “wink when they pray because they think themselves so perfect on the highway to heaven that they can find it blindfolded.”

Thomas Morton was exiled to Maine where in 1647 he died a broken man. Two centuries passed before his book would come to delight an irreverent literary crowd beginning with Nathaniel Hawthorne and ranging up to Philip Roth, who thought Morton should be on Mt. Rushmore. Reverential scholars sometimes sanctify the impious Morton, seeing his Merrymount as the embodiment of a tolerant, harmonious community. But the last word on Morton might go to historian and diplomat Charles Francis Adams who, after putting together the first scholarly edition of the New English Canaan (1883), judged Morton to be an absolute scoundrel but the only writer with the wit to see grim New England as comical.

Happy Thanksgiving to you and yours and thanks again to the NYSL for keeping the “overlooked” in circulation.

After earning a doctorate in history from the University of Chicago, Jim Wunsch served on the staff of the New Jersey General Assembly and the Regional Plan Association, a private, non-profit metropolitan planning agency. He later taught high school social studies in The Bronx and history at Empire State College (SUNY) where he is professor emeritus.

Disqus Comments