Here's Looking at You, Moby-Dick

Wallace Stevens chose for one of his poems the evocative title “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” If the small Turdus merula can inspire thirteen approaches, then the huge Physeter macrocephalus must be worthy of, oh, 1,300 or so. I see you accessing that latent part of your brain that contains Greek and Latin roots and coming up with “Something big-head.”

You’re right. A very big head…with one eye on each side of that big head. But what about “Physeter”? Only very very advanced students of classical Latin get to learn the noun for “bellows.” And now we need the mind of a poet to picture a big-headed, swimming mammal with a bellows-like action in the top of its head. If we turn that figurative fire-feeding bellows into a watery spout or blowhole, then we’ve conjured up a sperm whale.

Herman Melville (1819- 1891) had at least 1,300 thoughts about the white sperm whale that earns the title position of his most famous novel, Moby-Dick (1851). Let’s pare things down and deal with, say, three approaches to think about right now.

One: the historical approach. The Moby Dick that swam out of Melville’s brain had at least two real-life prototypes. A seemingly malevolent sperm whale rammed and sank the American whaler Essex in 1820. First mate Owen Chase wrote a book about this horrific incident and its ghastlier sequel (think cannibalism). By coincidence, in 1840 the sailor Melville’s shipmate was the teenaged son of Owen Chase, who lent him the book his father had written. You can read Chase’s volume – or go for Nathaniel Philbrick’s even more compulsive retelling, In the Heart of the Sea. (It won the National Book Award for nonfiction in 2000.)

Only a year later – 1821 - a real whale named Mocha Dick was sinking small craft with one fluke of his tail in the environs of Cape Horn. His name derives not from a color (Mocha Dick, like his fictional descendant, was albino) but from an island. Isla Mocha is about 40 miles off the coast of southern Chile. Melville learned about this whale from an 1839 article by Jeremiah N. Reynolds in a monthly magazine called The Knickerbocker.

(The name of Melville’s whale – Moby Dick – seemingly echoes the name Mocha Dick, but scholars are mostly at a loss for the origin of “Moby.” One writer’s guess: it derives from the obscure Shakespearean adjective “mobled” (veiled), but it’s easier to find descendants of “Moby” than ancestors.)

So much for our first approach, the historical. Let’s turn to the biographical. Since this is such an accomplished novel, may a new reader make the guess that it was the finale of Melville’s writing career? No, or “No, in thunder!” as Melville liked to characterize the philosophical approach of fellow novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Although Moby-Dick was the sixth novel of this amazingly fast writer, he was only thirty-one when he wrote this book. Thirty-one! (Hawthorne, by way of comparison, was in his mid-forties when he wrote The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables.)

The Melville family (Herman, his wife Lizzie, and toddler Malcolm) lived in Manhattan when he began writing this book, but he wrote the bulk of it in the house he named Arrowhead in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. (His six-miles-away neighbor was indeed Nathaniel Hawthorne, whom he met, with friends in common, on a climb up Monument Mountain on August 5, 1850. A year later he dedicated the completed book to Hawthorne, “In token of my admiration for his genius.”)

Good news: Arrowhead is preserved as a tribute to Melville, and you, like me, can stand by his desk in his second-floor writing room and get the shivers as you look out the window at the view of Mt. Greylock, just as the author did. Your shivers intensify when you read the final paragraph of Chapter One and understand Melville saw that mountain view as being very like a whale” (and vice versa): “...one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.” (Indeed, Melville dedicated his next novel Pierre (1852) to this mountain!)

Our third and final approach to this monumental novel is this - popular culture. A question: where did all these white whales come from? My own acquisitiveness and the kindness of friends have endowed me with a white whale coffee mug, a white whale Christmas tree ornament, a white whale tote bag, and white whale earrings. Much as I like novels such as The Great Gatsby or The Sound and the Fury (to name only two), I’ve seen no tchotchkes related to them. Only Shakespeare’s plays seem to have spawned an equal number of spin-offs.

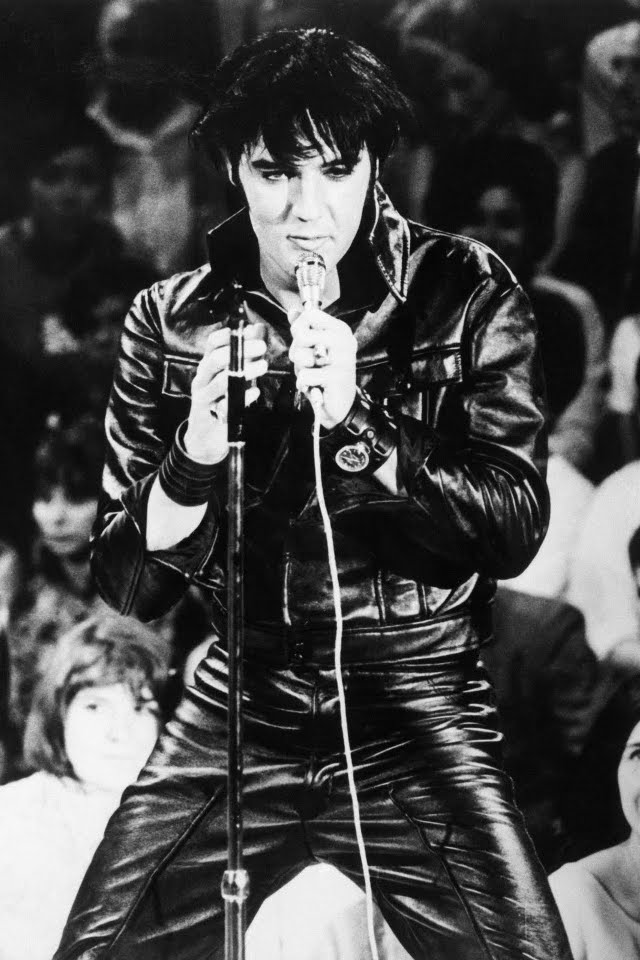

And then there’s the world of pop music. Did you know the legal name of the singer Moby is Richard Melville Hall, who says he may be the great-great-great nephew of the progenitor of Moby Dick? Are you old enough to remember Elvis Presley, in his ’68 Comeback Special, brandishing the microphone stand like a harpoon and shouting “Moby Dick” to the audience? Or the great Led Zeppelin number (drum solo of twenty minutes) named, yes, “Moby Dick” ? Or “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” which alludes to the whale and “Captain Arab” [sic]?

History, biography, popular culture. Popular culture? Starbucks. When the chain was in the works, the word Pequod (the name of the boat in the novel taken from the name of a tribe of Native Americans) was a nominee for the name. But the company settled for the appellation of the (cowardly or noble) first mate – Starbuck, who makes one of his appearances holding, yes, a coffeepot. Dwell on that when you order your next venti.

Final proof of pop culture status may lie in the realm of humor. An April 2020 New Yorker cartoon shows the deck of the Pequod with its commander captioned: “Captain Ahab took up meditation and yoga and eliminated caffeine.” In the foreground one sailor remarks to another: “He definitely doesn’t talk about the white whale as much.”

Disqus Comments