The Library at 265: Remarks by Jenny Lawrence at the 2019 Goodhue Society Celebration

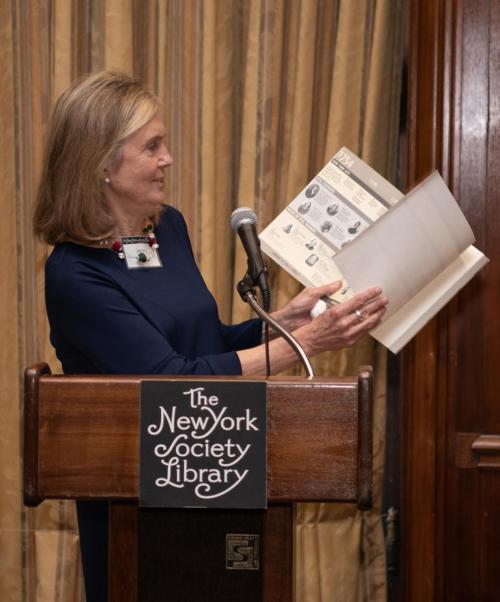

Jenny Lawrence (left) gave these remarks at the May 15, 2019 celebration of the Library's legacy group, the Goodhue Society. Ms. Lawrence served as a Library trustee for many years, founded the Library's newsletter in 1992, and co-created (with Henry S.F. Cooper Jr.) the 2004 volume The New York Society Library: 250 Years.

Carolyn asked me to prepare some remarks about the Library’s 250th anniversary book, published in 2004, which drew upon two previous histories of the Library: Austin Baxter Keep’s 1908 History and Marion King’s 1954 Books and People. Although Henry Cooper and I were the co-editors of the 250th history, many contributed to this effort, which was a year in the making. Sara Holliday was indispensable in shepherding the project to designer John Bernstein, who was responsible for the book’s spacious elegance and especially for the splendid illustrated, pull-out timeline front-and-back endpapers. Edmée Reit, who had been organizing the Library’s archives since the late 1970s, was a huge help. Apparently, the temperature in the Stack 8 archives is a mild 68 degrees these days, but I remember working in there with Henry that hot summer of 2003 in down parkas and gloves, sifting through letters, newspaper clippings, memos, minutes, and reports.

I have to say that Henry is mostly responsible for what makes this history zing. He became a trustee at age 36 in 1971, served as Board Secretary from 1979-1985 and Board Chair from 1985-1992, and actively served on the Board until his death three years ago. He could turn pedestrian prose, with a few deft edits, into a most readable form. He could pluck the right letter or clipping from the rich archival trove. He had an instinct for le mot juste, and his spirit is on every page. He should be here—I’m only pinch-hitting.

In rereading the 250th history, I was struck by the fortuitous chance outcomes that often shaped the Library’s course. Twenty years after it was founded in 1754 and given permission to keep its books in “The Library Room” in City Hall, the Library closed down altogether at the start of the American Revolution, its collection of books dispersed. Fourteen years later, when the Revolution ended, how easily the Library could have become a footnote in history, had not 600 of its 1,500 books been found in St. Paul’s Chapel, and others gradually returned from pre-war trustees to its second-floor home in City Hall. The next year, 1789, the city became the new republic’s federal capital, and City Hall where the U.S. Congress met—thus the second-floor Library became the de facto Library of Congress for the next five years, until the federal government was relocated to Philadelphia and then to Washington D.C. President George Washington, Vice President John Adams, Chief Justice John Jay, and many government luminaries borrowed books from the collection. Famously, Washington is suspected of borrowing but not returning Volume 12 of Emer de Vattel’s The Law of Nations. The question of whether or not it was actually checked out remains unresolved. Calls for this book have not exactly been clamorous over the years, but in case you want to peruse its pages, the volume has been replaced and is in our Special Collections, available by appointment only.

I was also struck by the important role of women in the Library’s history—starting with Anne Waddell—widow of a trustee—one of the original signers of the 1772 charter. From the beginning, the Library welcomed women members, unlike the Boston Athenaeum that believed it “undesirable that a modest young woman should have anything to do with the corrupter portions of the polite literature. A considerable portion of a general library should be to her a sealed book.” Women, especially widows, would be key to the Library’s fortunes.

By 1795, the Library moved further north to its second home on Nassau Street. Librarian John Forbes’ son Philip recalled the vicinity: “the view southward gave a vista of that fine, wide, well-built and handsomely planted avenue, Broad Street, then still the leading quarter of the early aristocracy of the town….” The Library sought to be in the neighborhood of its patrons.

Inevitably, after 45 years, the Library became a backwater. A rival, the New York Athenaeum, offered among its attractions a reference library, a reading room of newspapers and magazines, and a lecture department. But after a very few years, the rival experienced financial difficulties and approached the Library to join in “amicable vicinage” which prompted the selling of the Nassau Street home and the building of a new home on Broadway at Leonard. When the Athenaeum couldn’t afford to pay its fair share of costs and was dissolved, its members joined the Library’s. One of the legacies of the Athenaeum was an active lecture program in its auditorium with seats for 400. However reluctant the Library was to be in the lecture business, it did host, starting in February 1842, six extremely well-received lectures by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Walt Whitman was in the audience and later wrote: “The Transcendentalist had a very full house on Saturday evening. There were a few beautiful maids—more ugly women, mostly blue stockings*; several interesting young men with Byron collars**, doctors, and parsons; Grahamites***, and abolitionists; sage editors, a few of whom were taking notes; and all the other species of literati.”

After sixteen years, there was renewed pressure to move northwards. Fortuitously, Mrs. Adeleine E. Schermerhorn, widow of a Library trustee, wanted to sell the three lots next door to her house on University Place. But she didn’t want “any building save of brick or stone of at least two stories in height” nor to “erect, permit or suffer upon the said premises or any part thereof of any public school, trade, business, or occupation dangerous, noxious, or offensive to neighborhood inhabitants.” The Library, happy to rid itself of its public lectures, assured Mrs. Schermerhorn that it was a purveyor of non-noxious books and would be inoffensive to neighborhood inhabitants. Thus it was able to build their new home here—a mile and a half north from the Broadway at Leonard Street location. There we stayed 81 years, beginning in 1856.

The Library might still have been at University Place, even after Mrs. Schemerhorn’s house in 1928, “the Library’s red-brick and brownstone twin,” was replaced by an apartment house. Again, a generous widow—Sarah Parker Goodhue—left the handsomest of bequests to the Library in 1917 to go toward a new Library building as a memorial to her husband. According to Marion King’s history, Mrs. Goodhue was going to give the bequest to the Metropolitan Museum of Art but did not, because she disapproved of the Met being run by an Englishman. Happily, it went to the Library instead, which could boast that it was run by red-blooded Americans. The bequest wouldn’t be activated for 20 years, but in 1937 it was used to purchase and renovate the Rogers’ family’s five-story mansion at 53 and 54 East 79th Street into what we know today as the NYSL.

In 1973, four folios of the first edition of Audubon’s Birds of America were stolen from the Library, a shocking discovery. How could the so-called “Elephant Folios” have been slipped out from under the librarians’ noses without being detected? The full story is dramatically told in the 250th history. But the ultimate outcome of the theft greatly benefited the Library. Most of the prints were recovered and in 1981 auctioned off by Parke Bernet, netting the Library a whopping $1,118,318—used to renovate the Library top to bottom in the early 1980s.

What accounts for the resiliency that has enabled the Library not only to survive reverses but to continue to thrive all these years? I think it has to do with the fierce loyalty, affection, and support of its members. A good example is a letter in 1944 to Marion King at the Circulation Desk by a concerned reader.

Dear Mrs. King,

I was reading last evening As We Go Marching, by John T. Flynn, which you very kindly sent to me, and on the first and third pages, and I think on the eleventh page, I found in the margin in pencil, the word “shall” written in by somebody to correct what he deemed to be the error of the author in using the word “will.”

I know of no more depraved form of quadruped than a person who will write himself into a book in this way—and yet some do. I wish you could catch one of them and bring him into my court, where I think I would give him a life sentence on sight.

Sincerely,

Henry H. Curran, Chief Magistrate City of New York Magistrates’ Courts

Tributes from Library members included in the 250th history are equally supportive and most eloquent—like Benita Eisler, who wrote:

I can map my life using as coordinates the libraries I’ve used….Only the Society Library has ever seemed truly mine. I’ve witnessed its change from a charming, clubby enclave to a professionally administered institution, where such services as Interlibrary Loan and on-line resources make it increasingly unnecessary to leave the building. Evening lectures, conversations, and concerts have made the Library a more vibrant place….More astonishingly, these transformations have left the spirit unchanged; warm and welcoming, a refuge and a hideout, and, thankfully, a little eccentric still.

This is the third thing that struck me in rereading the 250th history, expressed in comments by members, whether in 1754, 1854, 1954, or 2004. For each of us, the Library is our own place, where we come to be alone—with ourselves, in the community of books. Fortuitous chance, good choices, a sensible bottom line, concern for individual members, generous bequests, especially from widows….Working on the 250th book with Henry—even shivering away in Stack 8 archives— gave me a marvelous perspective on the Library. It has evolved with the city—not upwards but certainly northwards. It serves as a memory keeper and has had a remarkable ability to adapt with the times while maintaining, as always, a concern and interest in every one of its members, and, above all, a reverence for the written word and for books.

Thank you.

*A bluestocking was an educated, intellectual woman, originally a member of the 18th-century Blue Stockings Society led by the hostess and critic Elizabeth Montagu (1720–1800).

**A soft shirt collar, often with long points, worn by Romantic poets such as Lord Byron

***One who followed the dietetic system of Sylvester Graham (1794–1851), an American Presbyterian minister and dietary reformer known for his emphasis on vegetarianism, the temperance movement, and eating whole-grain bread. His preaching inspired the graham flour, graham bread, and graham cracker products.

Photo by Karen Smul

Disqus Comments