Notes from an Intern: Developing Research Questions in Conversation with Librarians of the Past and Present

I was hired to join the Library’s effort to modernize the cataloging system for its First Charging Ledger in March 2015. At that time I little knew how far it would advance my knowledge and skills, or realized the social and historical considerations that would arise during my foray into the historical collection. In working with the library’s Special Collections staff and the Ledger project team, I have both gained practical experience in digital curation using cutting-edge collections management software, and travelled back into the convoluted organizational processes that occupied the minds of 18th and 19th century librarians.

My work with the content management database is likely not of great interest to anyone outside the Information Science professions, though I believe that some research questions generated by close engagement with the Library’s early catalogs may be worthy of greater investigation. My curiosity has so far led me to question the experience of women in the world of publishing, and female authorship, at a time when their social contributions were limited, and the ways in which issues of class division and latent prejudice infected even the realm of a librarian’s purely organizational categorizations. My interest in these themes was piqued by the obviously subject-specific segregation of novels from the rest of the alphabetical catalog in those records from 1800 onward, as well as the large number of works of popular fiction that were wholly excluded from the catalogs, despite their known presence in the collection.

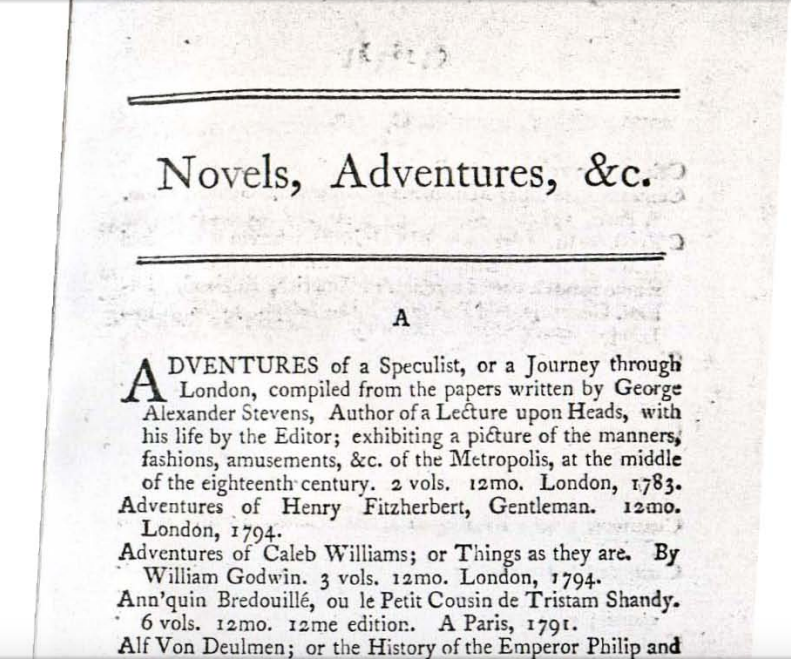

I began to notice these systematic deletions as I worked on entering background data into our new database about the volumes included in the library’s First Ledger. Several times in my process, I was assigned a record for a book that had several different readers listed alongside the dates of their readership, but I was unable to find the title anywhere in the historic catalogs. Once I had subdued my initial frustration with the task’s complication, I began to notice that in the overwhelming majority of instances where a title was left out of the library catalog, that book was a work of fiction. Those novels that were included in the catalogs were members of a somewhat sparse list, a list that seems to a modern investigator to be somewhat begrudgingly written. Often, even those titles that were well read at the time (though they were more likely to be included) seemed to have been deemed unimportant by the powers that were, those librarians in charge of creating the catalog record.

I began to notice these systematic deletions as I worked on entering background data into our new database about the volumes included in the library’s First Ledger. Several times in my process, I was assigned a record for a book that had several different readers listed alongside the dates of their readership, but I was unable to find the title anywhere in the historic catalogs. Once I had subdued my initial frustration with the task’s complication, I began to notice that in the overwhelming majority of instances where a title was left out of the library catalog, that book was a work of fiction. Those novels that were included in the catalogs were members of a somewhat sparse list, a list that seems to a modern investigator to be somewhat begrudgingly written. Often, even those titles that were well read at the time (though they were more likely to be included) seemed to have been deemed unimportant by the powers that were, those librarians in charge of creating the catalog record.

The realization that it was novels that suffered from this sort of segregation and exclusion only came to me in the midst of conversation with my colleagues on the Ledger project, who greatly enlightened my brainwave and, indeed, quickly turned it into a brainstorm. We began to discuss possible reasons for the excision of novels from the catalog record, including the idea that they simply weren’t quite highbrow enough. It could be the case that librarians of the time felt that romance novels and adventure stories—though the most prevalent mode of mass entertainment at the time—were not worthy enough to be acknowledged as a popular part of their collection. For it is true that these works of frivolity would have been tremendously well liked by the patrons of the Library—a fact that is attested by the long list of readers and loan dates listed in the First Ledger. It seems curious that professional record keepers would choose to neglect a section of their collection just because it was considered too ‘common,’ but it seems the classist structures of the day may have influenced even the strictest of proceduralists.

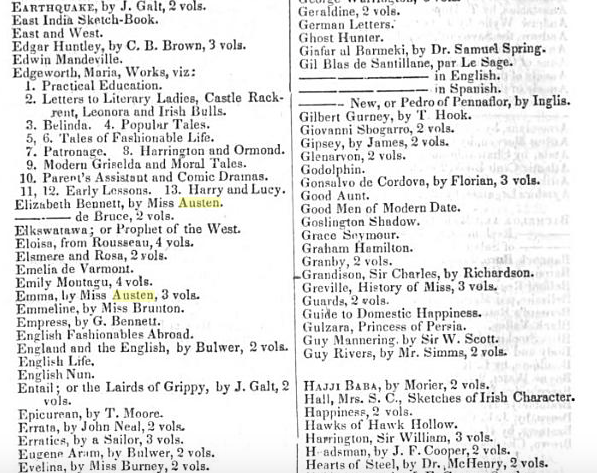

Another possible explanation for the avoidance of novels could have something to do with latent sexism, and a contemporary fear that fictional heroines and tragic female characters might encourage proper, decent women toward wildness, sexuality, and independence. It is conceivable that reputable academics, such as librarians, might have felt it dangerous to make such facetiae available to the respectable class of women who might have accessed the Library’s materials. At the very least, there is certainly an observable tiptoeing around authors of the female persuasion noticeable in the catalogs. For example, instead of a female author’s first and last names being listed next to the catalog entry for a particular title, as is the case with nearly all male authors in the catalogs, women writers are frequently referred to only as “Mrs.” or “Miss,” if their names are mentioned at all. Additionally, the limited information recorded on female authors of the period continues to have consequences today, as very little is now known about the backgrounds of many of these ladies. Their surviving identity records in historical databases are vastly smaller than those of their male counterparts, and, therefore, there is little for me to include in most of their author records in our database.

Another possible explanation for the avoidance of novels could have something to do with latent sexism, and a contemporary fear that fictional heroines and tragic female characters might encourage proper, decent women toward wildness, sexuality, and independence. It is conceivable that reputable academics, such as librarians, might have felt it dangerous to make such facetiae available to the respectable class of women who might have accessed the Library’s materials. At the very least, there is certainly an observable tiptoeing around authors of the female persuasion noticeable in the catalogs. For example, instead of a female author’s first and last names being listed next to the catalog entry for a particular title, as is the case with nearly all male authors in the catalogs, women writers are frequently referred to only as “Mrs.” or “Miss,” if their names are mentioned at all. Additionally, the limited information recorded on female authors of the period continues to have consequences today, as very little is now known about the backgrounds of many of these ladies. Their surviving identity records in historical databases are vastly smaller than those of their male counterparts, and, therefore, there is little for me to include in most of their author records in our database.

The sorts of questions that I have explored here have both plagued and fascinated me since I began work on the New York Society Library’s Ledger cataloging project, and by no means do I consider them answerable without further study. I do, however, feel that they are viable research questions that have grown from a project that never intended to give birth to them. It is true, of course, that the compilation of data such as that of the Ledger is completed in order to provide research access, and to lead historians to ask just these type of questions—but I never expected to be asking them myself. It seems that in the course of my work as a Library intern I have not only gained practical experience in a field to which I hope to devote my life, but I have also gained the opportunity to learn—and indeed to ask questions—at the feet of librarians from both past and present.

Disqus Comments