For Pride Month: A Taste of Queer Brooklyn

Guest blogger Hugh Ryan won a 2019-2020 New York City Book Award for When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History. Learn more about his current and upcoming work on his author site.

When I began the research for When Brooklyn Was Queer, one of the first things I noticed was that the story of Brooklyn’s early queer community was largely an economic one. That is to say, the urbanization of Brooklyn in the mid-19th century provided a plethora of employment that was (for one reason or another) more available or of interest to folks we would today call queer.

One of these categories of employment was artist. No, queer people are not naturally more artistic than our straight peers, but artists were often given leeway to be eccentric; expected to leave behind their communities and families of birth; not (as) expected to have children or prying business associates; and more likely to leave a record of their interior desires and thoughts. For all these reasons, they re-appear often in the records of queer history.

As such, Brooklyn has a rich history of queer writers to celebrate. Some of these people wrote about Brooklyn, while others did not, and still others were inspired by Brooklyn, but set their stories elsewhere. For all of them, however, Brooklyn provided a space of refuge – momentary or life-long – and their work deserves to be remembered when we celebrate the queer history of our city. These are just a few of the many, to get you started.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1855)

This is the ur-text of queer Brooklyn, if such a thing exists. Not only was Walt Whitman a long-term Brooklyn resident, but the book itself was written in part to celebrate the joys of urban life – one of those being the joys of meeting “them that love, as I myself am capable of loving” as Whitman wrote in “These I Singing In Spring.”

Mary Hallock Foote, A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West (1972)

Mary Hallock Foote moved to Brooklyn in the late 19th century in order to take art classes at Cooper Union, one of the few art schools that had programs for women at the time. She would go on to write and illustrate over 30 books about life in the American West, but her memoirs wouldn’t be published until much later. Her life-long romance in letters with Helena deKay Gilder (whom Foote met at Cooper Union) was the basis for Wallace Stegner’s 1971 novel Angle of Repose.

Alice Dunbar Nelson, Violets and Other Tales (1895)

Alice Dunbar Nelson (at right) moved to Brooklyn Heights right around her 20th birthday in 1895, just after she published her first book, Violets and Other Tales. While her writing provided her with fame and some income, she also moved to Brooklyn to work as a teacher in Weeksville, a predominantly black neighborhood that was on the forefront of school integration in America. (The link above is to our collection, but you can find the full text here courtesy of the Schomburg Center.)

Hart Crane, The Bridge (1930)

Hart Crane was enamored with the Brooklyn Bridge, which he saw as the ultimate symbol of America, connecting its mythic and romantic history (via Walt Whitman) to its modern present. When he moved to Brooklyn to write his masterwork, The Bridge, he lived at a storied (if now largely forgotten) address: 110 Columbia Heights. It was from that building that Washington and Emily Roebling directed the final years of work on the Brooklyn Bridge itself. Years later, it was purchased by Hamilton Easter Field, a queer artist and art patron from a well-heeled Brooklyn family, who turned it into an art school with cheap rooms for artists. Aside from Hart Crane, other residents included John Dos Passos, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Katherine Schmidt, and Stefan Hirsch.

The Double Man, W. H. Auden (1941)

The G String Murders, Gypsy Rose Lee (1941)

Two Serious Ladies, Jane Bowles (1943)

Black Boy, Richard Wright (1945)

The Member of the Wedding, Carson McCullers (1946)

The Ballad of the Sad Café, Carson McCullers (1951)

What connects a book of poetry, a pulp mystery, three literary novels, and a memoir, published over the course of a decade? All of these books were developed during, published in, or inspired by their author’s time living at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn during World War II. Painters, theater makers, composers, singers, musicians, and other artists across the spectrum of sexuality all flocked to this queer communal home, founded by author George Davis. “All that was new in America in music, painting or choreography emanated from that house, the only center of thought and art I found in any large city of the country,” wrote Swiss author Denis de Rougemont. (In the sidebar: 7 Middagh Street shortly before it was destroyed in the building of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.)

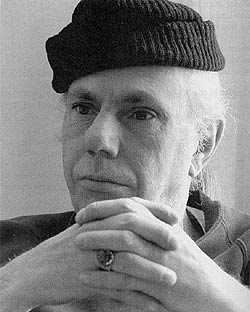

Only As Far As Brooklyn, Maurice Kenny (1971)

Maurice Kenny (at right) wrote more than twenty-five books of poetry in his lifetime, many of them drawn directly from his heritage as a member of the Mohawk Nation, and was twice nominated for a Pulitzer. Only As Far As Brooklyn was his first book with explicitly queer themes, and it collected poems Kenny had published in the underground queer magazine, Fag Rag. According to The Queerness of Native American Literature, Kenny is “the first known gay Native author to publish overtly queer literature in the United States.”

Disqus Comments