History Happened Here

by Thomas Fleming Copyright © 2010

How many other American libraries have had George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, John Adams and John Jay among their patrons? The answer of course is none. This is the most fascinating fact that the Society Library's first charging ledger documents and is perhaps the main reason we're here today to celebrate the ledger's rehabilitation as an historical document.

The ledger has had a history of its own as well as recording it in its three hundred pages. Sometime in the 19th century it disappeared and no one seemed to know what had happened to it. In 1934, a staff member in the Library's fourth home, at 109 University Place, discovered the ledger in a basement trash pile. It would have undoubtedly been thrown out when the Library moved uptown to our present quarters three years later.

Instead, the ledger traveled to this far more spacious building, giving us a marvelous chance to peek into the reading habits of several hundred prominent New Yorkers, as well as the peregrinating members of our new national government, such as President Washington and Vice President Adams.

Before we get to these historic reading habits, there is another story worth telling. From 1754, the date of our founding, the Library had steadily accumulated members and books. By the time the American Revolution erupted in New York, it had an estimated 1300 volumes—a formidable collection in those days when books were printed and stitched together by hand. Their home was an ample room in the old City Hall on Wall Street.

In 1776, George Washington's Continental Army was driven from New York by the invading British. Congress had sternly directed him to keep the city intact. Washington, rapidly becoming a master of clandestine warfare, looked the other way while teams of incendiaries set New York ablaze to deprive the British of winter quarters. Later the general attributed the conflagration to Divine Providence or "some good honest fellow."

About twenty percent of New York's buildings, including Trinity Church, became charred ruins and in the ensuing chaos, the Society Library's collection was looted by infuriated British soldiers and sailors, who sold the books at nearby grog shops for a few gulps of rum. The Library more or less ceased to exist.

In 1788, New York became the capital of an independent nation with a new constitution and new government. A plaintive notice appeared in the newspapers, asking "such persons who have in their possession any of the books belonging to the New-York Society Library" to return them to any of several trustees. A surprising number of books surfaced. Six hundred were discovered somewhere inside St. Paul's Chapel, apparently hidden there and forgotten for the previous decade.

In 1789, the Library reopened in the same building on Wall Street, remodeled and christened Federal Hall. It now housed not only the city government but also the two branches of the new congress and the offices of the president and vice president. Some people have argued that this cozy relationship with the federal government entitles us to claim we were the first Library of Congress.

I fear this is a bit of stretch. If anyone deserves that unofficial title, it is the Library Company of Philadelphia, which opened its shelves to the 1774 Continental Congress and continued the policy until Congress retreated to Princeton in 1783 to escape bayonet-wielding soldiers demanding back pay.

Nevertheless, our historic flirtation with the new federal congress may behoove us to ponder the way our predecessors managed to team up with the nation's political arm, giving the Library a sort of semi-official aura.

Does this suggest we ought to consider laying our contemporary hands on some federal stimulus money? We could argue that it's one of our hallowed traditions.

Let's leave that one to the trustees and move on to the famous names that began appearing in the charging ledger in 1789. President Washington took out one volume of a series devoted to the debates of the British Parliament and a second book, The Law of Nations by a Swiss historian named Emer de Vattel. This book was one of the first attempts to create a workable set of international laws.

The Vattel book has serious historical significance. I plan to discuss it in a book I'm writing about George Washington's presidency. One of his primary goals was to assert the authority of his new office in the field of foreign policy. The Mattel book dovetails neatly with something else Washington did in his first few weeks as president. He sent letters to the rulers of every nation in Europe, informing them that if they wished to conduct any business with the new United States, they should write to him—not to Congress.

Congress had demonstrated a notable ineptitude when it tried to conduct foreign affairs through various committees. They finally appointed a secretary for foreign relations but he had little or no authority. Neither did the president of Congress, who was a powerless figurehead.

The next federal customer in our charging ledger was Vice President John Adams. He appeared personally in the Library to take home Volume I of Elements of Criticism by the noted Scottish writer, Lord Henry Kames. If Honest John, as Adams called himself, had known this was one of Benjamin Franklin's favorite books and Lord Kames had been one of Ben's most fervent admirers, I'm sure he would never have gone near it.

Adams and Franklin did not become friends during the several years they spent in Europe as fellow diplomats. Honest John wrote numerous letters to Congress claiming that Franklin indulged in orgies with Frenchwomen. Ben informed Congress that Adams was "always an honest man, often a wise one but sometimes and in some things absolutely out of his senses."

In these first days as vice president, John Adams demonstrated this latter trait to a dismaying degree. He informed the U.S. Senate that he thought George Washington's title should be: "His Highness, the President of the United States." In letters and formal addresses, he recommended calling Washington "His Majesty." He thought the vice president deserved the same title.

Fortunately for the stability of the republic, James Madison, the man who wrote most of the Constitution, was in Congress. Probably after consultation with Mr. Washington, with whom he was on intimate terns, Madison persuaded the House of Representatives to vote overwhelmingly to address the leader of the nation as "Mr. President.'

The vice president became the butt of jokes. A senator from South Carolina won the biggest laugh by suggesting John be called "His Rotundity." Alexander Hamilton, newly appointed as Secretary of the Treasury, borrowed two novels, The Amours of Count Polviana and Eleanora, and, according to the ledger, A history of Edward Mortimer which the librarian briskly noted was written "by a lady."

Both choices suggest two things. Mr. Hamilton was confident he needed no additional information on government finances—and he may have been having problems juggling his affection for his devoted deeply religious wife, and his passionate attraction to his shapely sister in law, Angelica Schuyler Church.

Aaron Burr revealed the two sides of his complex nature in his book selections. His first choice in 1789 was Revolution in Geneva, devoted to the tumultuous history of that early venture into radical Protestant government. Next came a volume by Jonathan Swift, followed by the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon.

In 1790 Burr became devoted to the famous French skeptic, Voltaire, devouring no less than nine volumes of his anti-establishment essays and satires. Simultaneously he was enjoying two novels, Mysterious Husband, and False Friend, titles which can be used to further blacken his reputation.

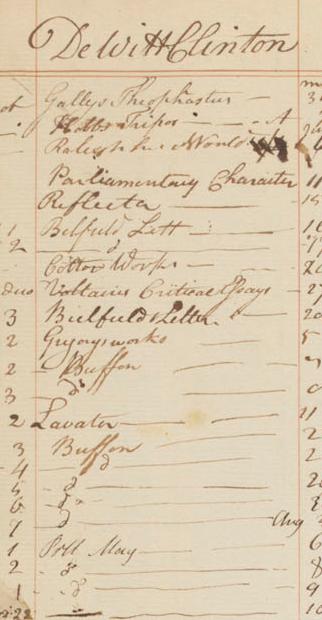

I'm one of the few historians who decline to dismiss Burr as a scoundrel. I see him as a victim of one of the most savage political massacres by slander any American politician has ever undergone. The man in charge was the president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. The chief scandalmongers were those two esteemed citizens of our city, DeWitt Clinton, mayor of New York, and his uncle George, the governor of our great state. Together these gentlemen destroyed Burr when he dared to run for governor of New York on the Federalist ticket. I tell the nasty story in detail in my 1999 book, Duel, a joint biography of Burr and Hamilton.

Back to our charging ledger. The last of the famous patrons is John Jay, one of the architects of the peace treaty with Britain that ended the American Revolution and the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. If I listed all the books Jay took out, we would be comatose long before I got halfway through. They ranged from Don Quixote to Plutarch's Lives to Captain James Cook's report on his circumnavigation of the globe. Jay and his descendants remained active members and supporters of the Library well into the 20th century.

When it comes to historical excitement, we're only warming up. Hidden in the charging ledger's pages is shocking information about the greatest of our early patrons, George Washington. It has to do with something we seldom associate with Washington—failure.

In 1791, after little more than a year in New York, Congress succumbed to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson's dislike of large cities and his even more intense dislike of a stock exchange and voted to move to Philadelphia for ten years, while a new "federal city" was built in a wilderness we now call Washington D.C. It was the price Jefferson exacted for agreeing to Alexander Hamilton's brilliant plan to create a Bank of the United States and pay off the national debt by selling shares in it.

In the sound and fury surrounding this debate, President Washington departed for Philadelphia without returning Emer de Vattel's book on international law. No doubt the keepers of the Library's charging ledger were well aware of this failure. But they hesitated to badger the president of the United States.

Perhaps they convinced themselves that Washington continued to find the book useful. In 1792, the French Revolution exploded into an all out war with Great Britain and several other European states. Washington decided the United States should remain neutral in this huge imbroglio. To further assert the power of the presidency, he waited until Congress adjourned to issue his declaration. Pro-French congressmen and others, notably Thomas Jefferson, were infuriated and made life very uncomfortable for the president for the next four years.

Nothing was said or done on the library's side of the story and President Washington went home to Mount Vernon at the end of his second term with the Vattel book in his luggage. By this time the great man was sixty five years old and growing forgetful. He sold a handsome desk to the widow of the mayor of Philadelphia, and she found in one of its drawers a packet of his letters, which she breathlessly informed the ex-president, were written to "a lady!" Only much later in her teasing letter did she reveal that the lady was Martha Washington.

Washington liked to correspond with flirtatious women. He told this vamp, who incidentally was very pretty, that if a reader of the letters hoped to warm her or himself with the flame of a romance, she or he would be well advised to light a fire instead. But the letters were rich in something better than romance: friendship. It was one of his most touching tributes to his four decades of marriage with the former Martha Dandridge Custis.

Fast forward to the 21st century. The charging ledger is on its way to rehabilitation and details of its contents are beginning to circulate. Little did we realize that the omnipresent media of our time might find it interesting, even titillating to report that George Washington wasn't perfect, after all. Suddenly there blossomed in various newspapers such as the Christian Science Monitor, the Guardian, and the New York Daily News a report on the Vattel book with an estimate that Mount Vernon owed the Society Library at least three hundred thousand dollars.

This figure is much too low. If we start translating 1790 money into current dollar values, the price of the debt skyrockets by a multiple of at least twenty. If President Obama keeps depreciating the dollar, the figure may soon rise to multiple of forty. I estimate we're looking at a possible debt of $32,000,000.

At this point I have to wonder if fantastic visions danced through the heads of our leaders, Chairman of the Board Charles Berry and Library Director Mark Bartlett. Did they see themselves in a court of law, listening to a judge declare them - in the name of the Society Library - the principle stockholders in the corporation that now operates Mount Vernon? Did they imagine themselves on the verandah of the mansion, enjoying the superb view of the Potomac River, and summoning one of the members of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association to serve congratulatory mint juleps?

Alas, this Berry-Bartlett triumph wasn't to be. The man who runs things at Mount Vernon, Executive Director James Rees, decided that it was time to take the initiative. Mr. Rees summoned Joan Stahl, HIS librarian, and said: "Find a copy of that Vattel book. Price is no object. I wouldn't be surprised if these New Yorkers see this as revenge for the way the General—er, I mean some good honest fellow—tried to burn down their city in 1776!"

Of course I don't know whether Mr. Rees really said that. But it would be convincing dialogue in an historical novel, which I also like to write.

Ms Stahl went to work and presto!—for a mere $1,200 dollars, she found a copy of the missing book. Some media mavens, getting things wrong as they often do, said the price was twelve thousand dollars.

Soon there was a meeting here at the Library. I was honored to be among the invited members. Mr. Rees and Ms Stahl handed over the missing volume to Chairman Charles Berry, who graciously announced that any and all overdue fines would be considered paid in full.

Mr. Rees paid us a compliment in return. He chose our Members' Room as the place to announce Mount Vernon's plans to build a $150 million dollar library at Mount Vernon, devoted to scholarship on Mr. Washington.

Don't for a moment think the history that has streamed through the Society Library's portals ends here. It continues for another 220 years. There is a wonderful memoir by Marion King, Books and People, which I urge everyone to read. Perhaps the Library will consider republishing it to make it more widely available.

Mrs. King came to work for the Library in 1909 and stayed until 1954. Her account teems with vivid pen portraits of the Library staff before and after those years. There is a wonderful glimpse of Helen Ruskell coming to work in July 1920, at the age of 18. She was still presiding at the front desk when I arrived in the 1960s.

There are marvelous anecdotes, many from the old University Place headquarters. One day a gentleman tottered in, obviously very drunk. He wobbled to the large pictures on the walls, bowed his head and muttered to himself. It dawned on Mrs. King that he thought he was in a chapel and was reciting the Stations of the Cross. After fifteen minutes, he blessed himself and stumbled happily into the street.

Even better is a gentleman who took advantage of the standing rule that the Library is open to the public for research. He explained he was a genealogist and soon had a dozen or so books around him in the reading room. He liked the surroundings so much, he came back every day for the next 32 years.

Best of all are Mrs. King's recollections of her friendship with Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt. Some of you may have seen the exhibit of their letters in the Peluso Gallery not long ago. In some ways it's more interesting to read about these two remarkable women in the ongoing context of Marion King's relationship to the Society Library.

That way it's a sort of bonus while around them streams Mrs. King's priceless memories of fellow workers and patrons, such as the dignified lady who carefully pointed out "immoral" passages in almost every novel she took out. Even more memorable are her recollections of the writers who skyrocketed onto the best seller lists, forcing the Library to buy as many as 40 copies of their books. In almost every case, both the writers and the books are totally forgotten today.

It's sobering to see the rough game history plays with writers' reputations. But it also helps us understand the importance of this institution, where the forgotten books and writers live on, waiting to be rediscovered by the mysterious force that David Halberstam calls "the serendipity of the stacks."

Mr. Halberstam's essay on the Library is on our website and shouldn't be missed. He tells some very good stories. Perhaps his best describes how Truman Capote struck up a conversation with a dignified elderly woman in the Members' Room and invited her to join him for a cup of coffee. Capote remarked that he had just finished a wonderful book, My Antonia, and urged her to read it. "Actually, I wrote it," the lady said and introduced herself as Willa Cather.

Is there an historical lesson to be learned from this celebration of our charging ledger? As a serious historian, I gave this question hours of thought. I concluded George Washington's story should warn all of us to get our books back on time. You don't want the Society Library to suddenly foreclose on the nice vacation home your descendants of the 23rd Century have just bought --- on Mars.