Overlooked Books: James Wunsch on Three New York Memoirs

After earning a doctorate in history from the University of Chicago, Jim Wunsch served on the staff of the New Jersey General Assembly and the Regional Plan Association, a private, non-profit metropolitan planning agency. He later taught high school social studies in The Bronx and history at Empire State College (SUNY) where he is professor emeritus.

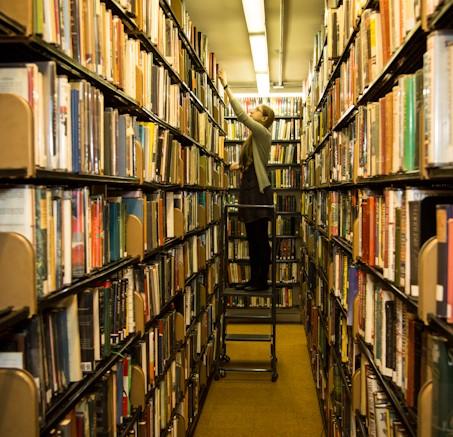

Last year, the Head of Acquisitions, Steve McGuirl, asked me to identify books which, if discarded, would not diminish the quality of collections related to urban studies, my ostensible field of expertise.

However gratifying it was to make room for new acquisitions by consigning superfluous books to new homes elsewhere (or, occasionally, the pulp mill), what really made the job interesting was the discovery that among the undistinguished or outdated, were certain other volumes which, though infrequently checked out, were sometimes more compelling or inviting than books frequently considered “essential reading.”

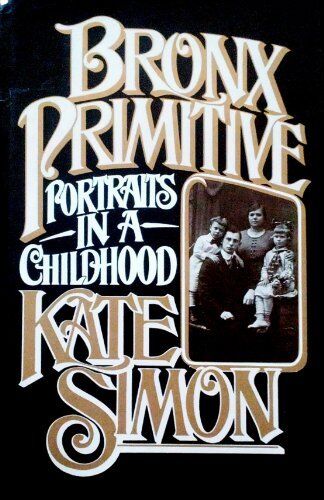

Consider memoirs that tell the story of three generations of New York women: Janet McDonald’s Project Girl (1999), the coming-of-age of a Black girl in Brooklyn during the fifties and sixties; Kate Simon’s Bronx Primitive (1982), the remembrance of being a Polish/Jewish girl growing up in a Bronx tenement in the twenties, and Sara Josephine Baker’s Fighting for Life (1939), an account of how a privileged girl from Poughkeepsie subdued Typhoid Mary before becoming a renowned advocate of preventive medicine.

Janet McDonald grew up in the Farragut Houses, a public housing project in a working class neighborhood near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. When Farragut opened in the early fifties, it was considered a desirable place to live. But as McDonald explained, the departure of upwardly mobile families contributed to the concentration of others dependent on welfare. By the early sixties, growing numbers of Farragut girls found themselves coping with unplanned pregnancies and the feeling of being overwhelmed by childcare responsibilities. Their brothers were drawn into drug dealing and criminal violence.

McDonald escaped. A talented student, she attended high school outside her neighborhood before going on to earn degrees from Vassar, the Columbia School of Journalism, and NYU Law. She served as an associate in a prestigious New York law firm and then established herself as an attorney in her beloved adoptive city, Paris. An inspiring story of how talent, hard work and being good at school allow one to escape the destructive forces of the city?

Not quite. Rather, this survivor’s testament seeks to reconcile personal achievement against deep-seated feelings for the desolation and despair of those left behind. When she returns to the projects, McDonald symbolizes all that can be achieved when you set your mind to it. But because she knows how project life overwhelmed her brothers and sisters, she is painfully aware of the odds against the Farragut kids.

McDonald is up against more than survivor’s guilt and a hyper-competitive legal community. She was raped, not at Farragut, but on Cornell’s bucolic campus. In throttling her fear and anger resulting from the assault, she starts carrying a knife and gun and then, out of sheer rage, sets fire to the trash cans at NYU Law which she was attending. The passage of time and helpful therapy allow her to regain a measure of health and to graduate from NYU , but she is never quite the same.

Alas, Project Girl is no period piece. Written a quarter century ago, its concerns remain ours today.

***

Kate’s Simon’s East Tremont neighborhood in the twenties was a good deal safer than what Janet McDonald had to contend with thirty years later. In fact, on Simon’s very first day of school, her mother tells the first-grader to take her brother by the hand and walk him to kindergarten while cautioning, “don’t talk to strange men.”

Kate’s Simon’s East Tremont neighborhood in the twenties was a good deal safer than what Janet McDonald had to contend with thirty years later. In fact, on Simon’s very first day of school, her mother tells the first-grader to take her brother by the hand and walk him to kindergarten while cautioning, “don’t talk to strange men.”

Here then is a neighborhood safe enough for even small children to walk alone, but still not without its perils. A nurturing Jewish family, we presume, might have served as a refuge. But in Bronx Primitive, Simon’s father comes across as an abusive character. At times, parental quarreling reaches the point where the street feels safer than the home. The movies and the public library emerge as most inviting of all.

Of course, marriage at this time appeared as the ultimate refuge. But Simon’s uneducated mother advises not to get married until “you can support yourself or better still don’t get married at all.” Simon was astonished: “I don’t want to report her as altogether eccentric, but in our [Jewish-Italian-Polish] community, girls were to marry as early as possible, the earlier the more triumphant... .” She holds off for a while and eventually writes the best-selling New York Places and Pleasures (1959) followed by other erudite, witty and appealing travel books. But among her works, Bronx Primitive stands out—a coming of age memoir that bears comparison with such classics as A Walker in The City (1951) by Alfred Kazin and Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943).

***

In Sara Josephine Baker’s Fighting for Life, childhood begins as a Victorian idyll—clam bakes, boating parties, and ice skating on the Hudson. Growing up in a cultured, well-connected Poughkeepsie family, she is destined for Vassar, her mother’s college.

Then it all comes crashing down. Within months, typhoid kills her brother and father. Without enough money to attend Vassar, and needing to help support the family, Baker decides to become a doctor, a not entirely respectable or even remunerative profession for a genteel young woman.

She enrolls in the Medical College of the New York Infirmary, founded by the sisters Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell, doctors who wished to make it possible for other women to study medicine. After graduating and completing her internship in Boston, Baker struggled to expand her practice in New York and so in 1902 decides to join the New York City Department of Health.

She enrolls in the Medical College of the New York Infirmary, founded by the sisters Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell, doctors who wished to make it possible for other women to study medicine. After graduating and completing her internship in Boston, Baker struggled to expand her practice in New York and so in 1902 decides to join the New York City Department of Health.

A few years later, city medical sleuths began to suspect that one Mary Mallon, a cook for the wealthy, might be infecting family members with typhoid. As Mallon resisted orders to be tested, the Department of Health summoned not only the police but also one of its own, Dr. Baker, who now appeared, not as that genteel girl from Poughkeepsie, but a no-nonsense plain-spoken woman accustomed to taking on all sorts of unpleasant tasks including vaccinating Bowery bums. In this case, Baker brings the furiously struggling Mallon under control. Tests showed that in failing to wash her hands prior to preparing food, Mallon, though showing no symptoms herself, was causing lethal outbreaks of typhoid.

Although invariably linked to Typhoid Mary, Baker created a sensation during the World War I era by warning that American infants were at greater risk of dying than troops fighting overseas. One in three New York kids perished before the age of five—the highest mortality rate of any city in the country. Working at the Health Department, Dr. Baker began teaching immigrant mothers in Hell’s Kitchen how to bathe, feed and clothe babies. She encouraged breast feeding and, when necessary, bottle feeding with formula she developed. She stressed that to be healthy, babies also needed to be hugged and loved. She set up clean milk stations in the poorest neighborhoods and worked to ensure that trained nurses were assigned to public schools. She successfully advocated for the licensing of midwives. No one had ever undertaken such a well-organized popular and practical teaching and training program. By the time she retired in 1923, New York had the lowest infant mortality rate of any other large US city. Thanks to her efforts, an estimated 90,000 infants were saved. Baker, unlike many memoirists, does not indulge in self-congratulation or sentimentality. A staunch advocate of birth control, she concludes by asking why, if you can prevent conception, would you choose to have children at all?

S. Josephine Baker, Kate Simon, and Janet McDonald repose, at least in book form, in stack number seven. You might check out their books and, in doing so, partake of that great joy: browsing in a wonderous “open stack” library!