Reading Country Music - by Gayden Wren

It’s a long way from New York to Nashville, from the Metropolitan Opera to the Grand Ole Opry. For armchair travelers, though, it’s a short trip. The Society Library’s collection includes a number of books about country music and country musicians. Here’s a sampling, reviewed by Gayden Wren. A list of further reading follows Gayden's selections.

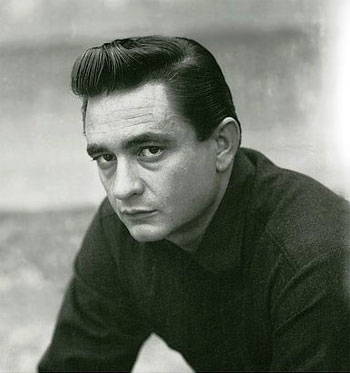

Cash: The Autobiography, by Johnny Cash (Harper, 1997).

Cash wrote two autobiographies, covering largely the same ground; the other was Man in Black: His Own Story in His Own Words (Zondervan, 1975). This is one is the more thorough and generally the more accurate. It’s heavily slanted toward where the 65-year-old Cash was in his life at this point, which means that you shouldn’t look here for much that’s unfavorable to his second wife, June Carter Cash, or more than grudgingly favorable to his first wife, Vivian Liberto Cash. However, by this point Cash was a devout Christian and very conscious of his own mortality, and he’s unsparing toward himself. The book is loosely organized and sometimes the chronology is hard to track, but it’s worth reading.

Hank Williams: The Biography, by Colin Escott (Little, Brown, 1994).

Escott, one of the best living country-music scholars, delivers what remains the definitive Williams biography, a balanced portrayal of the deeply flawed man whose mark on country remains indelible, almost 70 years after his death. It’s not a pleasant story—Williams wasn’t a pleasant man—but it’s fascinating stuff, told with scholarly attention to detail.

Lost Highway: The True Story of Country Music, by Colin Escott (Smithsonian Books, 2003).

Not really. Escott is a brilliant scholar of country music, and there are some nice nuggets herein (and some great pictures). But it’s the companion volume to a documentary series of the same title, and not the Ken Burns one you’re thinking of. It’s a quick read, but it’s nothing substantial for either the introductory reader (read Bill C. Malone) or an aficionado looking for something deeper (read Hemphill).

The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music, by Paul Hemphill (Simon and Schuster, 1970).

Probably still the best book ever written about country music as an art form, at least for its era, perhaps because Hemphill was not a devotee but rather a curious outsider who was interested in the South and its culture, and only incidentally in country music. He was also writing at a fortuitous time, when foundational figures like Sara and Maybelle Carter, Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb and Bill Monroe were still around, but latter-day giants like Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson and Willie Nelson were making themselves heard. Still required reading for anyone who loves the genre.

The Good Old Boys, by Paul Hemphill (Simon and Schuster, 1974).

Some of the pieces in this collection of journalism by Paul Hemphill focus on country music, but it’s the soundtrack to the whole book. Hemphill was a groundbreaking scholar on Southern culture in the second half of the 20th century and its roots, and country music is a big part of that … but only a part. As essay collections tend to be, this one is uneven and somewhat dated, but Hemphill was a smart man who’s still worth reading

Listen to the Stories: Nat Hentoff on Jazz and Country Music, by Nat Hentoff. (Harper Collins, 1995).

I haven’t read this book, but I’ve read some of the essays collected in it. Hentoff was a great music critic, but most of the pieces here seem to be about jazz, and that was clearly his primary interest. His insights into country music aren’t wrong, but they’re superficial; it’s hard to escape the sense that he wrote about country occasionally because he knew that Charlie “Bird” Parker loved country, and wanted to figure out why.

Johnny Cash: The Life, by Robert Hilburn (Little, Brown, 2013).

Hilburn adds some detail to Streissguth’s 2006 portrait of Cash, and corrects a few errors, but his take is largely the same. Cash was a man of many dimensions—a country singer, a pop singer, a folk singer and a gospel singer, as well as a civil-rights activist, a devout Christian, an absent husband and father, a devoted husband and father, and a man whose politics were an unusual mix of liberal and conservative positions—and Hilburn labors to tie his various personae together, with considerable success.

Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, by Charles L. Hughes (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

I haven’t read this one, but the subject matter is certainly promising. The story of country music is interwoven with the story of race in America and, especially, the South. Country icons such as Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family and Hank Williams were intimately influenced by the music of black artists, even during the years when black country singers were rarely heard … years which have yet to end. Hughes employs a "labor-based analysis" to explore what he calls the “country-soul triangle:" Memphis to Nashville to Muscle Shoals. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Barry Mazor called it "a deep, fresh examination of various power relations involved in the making of soul music, country music and the sonic space between them. Well-researched and analytically sharp, Mr. Hughes’s interpretation upturns the conventional narratives of music making." I’ll have to catch up with this one myself.

I’d Fight the World: A Political History of Old-Time, Hillbilly and Country Music, by Peter La Chapelle (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

This is a very new book with which I’m not familiar. The subject is an interesting one, though, and far deeper than the traditional take that country was liberal (in an FDR way) until 1969, and has been conservative (in a Merle Haggard way) ever since. La Chapelle traces the sometimes surprising bonds between country music and politics, from nineteenth-century fiddler-politicians to more recent figures. A recent review in the Journal of Popular Music Studies calls it "a vital new study...[with] a fresh perspective on the way genre and technologies of mass communications have shaped modern politics...[making] a compelling case that country music campaigners planted the seeds of the modern celebrity-politician." I look forward to reading it.

Satan Is Real: The Ballad of the Louvin Brothers, by Charlie Louvin (It Books, 2012).

Ira Louvin was a lying, cheating, hard-drinking, woman-chasing piece of work whose early death surprised few who knew him; Charlie Louvin was a cheerful, generous man who seemed never to lose his smile. Unfortunately Ira was the talented one, and Charlie never really managed to put together a solo career in the almost half-century between his brother’s death and his own. His book has some funny stories, but he’s not interested in really exploring who his brother was and how he got that way, so calling this a “ballad” rather than a “biography” is a good thing.

Coal Miner’s Daughter, by Loretta Lynn, with George Vecsey (Henry Regnery, 1976).

Lynn’s story is in some ways a typical country star’s rags-to-riches tale, but it comes with lots of specific detail and the same rich voice that informs her songwriting. Those who’ve seen the  Oscar-winning movie will know the story, but Lynn’s narrative voice adds depth and insight. Some of the details have been proven false (notably her claim that she was a 13-year-old bride—she’s subsequently admitted that she’s two years older than she claims in the book), and her subsequent book Still Woman Enough (Hyperion, 2002) revealed that Coal Miner’s Daughter was a cleaned-up version of the truth (her husband, Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn comes off even worse in the retelling). Even so, this is the greatest country autobiography of them all.

Oscar-winning movie will know the story, but Lynn’s narrative voice adds depth and insight. Some of the details have been proven false (notably her claim that she was a 13-year-old bride—she’s subsequently admitted that she’s two years older than she claims in the book), and her subsequent book Still Woman Enough (Hyperion, 2002) revealed that Coal Miner’s Daughter was a cleaned-up version of the truth (her husband, Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn comes off even worse in the retelling). Even so, this is the greatest country autobiography of them all.

Country Music U.S.A., by Bill C. Malone (University of Texas Pres, 1968, updated 2002).

The foundational book of country-music history (and, to a modest degree, criticism) has been superseded by other works in the past 50 years, but remains worth reading for its exploration of the rich fabric of early country music and Malone’s passion for the music itself. He buys into the hype more than later writers, admittedly, but the book still sings.

Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America’s Original Roots-Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century, by Barry Mazor (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Mazor is onto something in his approach to Rodgers, a fascinating character in his own right (see Nolan Porterfield's definitive biography below), but most significant in his impact on others. Mazor’s writing is uneven, and he sometimes skims lightly over aspects of Rodgers’ legacy that cry out for more explanation, but he’s thought about his subject deeply, and it shows.

Willie: An Autobiography, by Willie Nelson (Simon and Schuster, 1988).

Nelson has always been a storyteller, and this book—largely superseded by Nelson’s It’s a Long Story: My Life (Back Bay, 2015)—is more a collection of stories than a book per se. It’s strongest early on, recounting his early struggles, but can be frustrating in later years, as he talks exhaustively about, say, golf, while only occasionally delving into the music that made him worth an autobiography. And, of course, it stops more than 35 years ago, and Nelson is still active today at 88. Go with the later book, if you can find it. If not, many of the stories in this book are entertaining and reveal Nelson to have (besides a healthy self-regard) a good sense of character and a keen eye for the telling anecdote.

Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America’s Blue Yodeler, by Nolan Porterfield (University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

Nobody savored the Jimmie Rodgers myth more than Rodgers himself, who was the biggest contributor to its creation. He loved to spin colorful stories about himself, even (especially?) if they didn’t happen to be true, and many of them have become canonical. (Example: The “Singing Brakeman” wasn’t a brakeman and only briefly a railroad worker—he was a professional entertainer for most of his brief life. The widely disseminated photo of him in a brakeman’s outfit was a publicity still from a Hollywood movie.) Porterfield has done yeoman’s work in winnowing truth from fiction in a brilliant study of Rodgers’ life that will remain definitive for years to come. Its biggest revelation: The truth about Rodgers was as unlikely and as colorful as the lies.

Can’t You Hear Me Callin’: The Life of Bill Monroe, by Richard D. Smith (Little, Brown, 2000).

Two things on which almost everyone who knew Bill Monroe can agree: He was not a nice man—he was egotistical, uncompromising, controlling, temperamental, curt, womanizing, vindictive and sensitive to imagined slights. And Monroe was a brilliant musician, one of a handful of people who shaped country music as we know it today. Smith’s biography of the self-proclaimed “Father of Bluegrass” addresses both aspects of the man and, necessarily, how they reinforced one another: Monroe was never easy to work with, and yet world-class musicians fought to work with him—and, yes, often regretted it. His artistry was that great, and his personality was that rough. Smith’s book is broadly sympathetic to Monroe, but he doesn’t shy away from the other side of the story. (Also see The Bill Monroe Reader, edited by Tom Ewing.)

Man of Constant Sorrow: My Life and Times, by Ralph Stanley (Gotham Books, 2009).

Stanley, whose life spanned almost exactly the history of commercial country music (he was born a few months before the famous Bristol Sessions of 1927, and lived until 2016), was never a top star, either as a member of the Stanley Brothers or as a solo act, but his 70-year career was marked by consistent brilliance, as a singer and as a banjo player. He knew everybody, and his folksy book is full of sharp character portraits—notably the notoriously prickly “Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe, with whom Stanley had a long and tumultuous relationship. [Robert Cantwell's Bluegrass Breakdown: The Making of the Old Southern Sound (University of Illinois Press) is an excellent history of bluegrass, featuring Monroe, Stanley, and many more. —Ed.]

Johnny Cash: The Biography, by Michael Streissguth (Da Capo Press, 2006).

Written a few years after Cash’s own memoir, Streissguth’s book is a good one. He’s talked to many people who knew Cash, especially in his early life, and many friends and family members.  Most usefully, he has a more objective perspective than any previous treatment of Cash, and treats the singer’s personal life more candidly than the singer himself did.

Most usefully, he has a more objective perspective than any previous treatment of Cash, and treats the singer’s personal life more candidly than the singer himself did.

Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone?: The Carter Family and Their Legacy in American Music, by Mark Zwonitzer (Simon & Schuster, 2002).

A welcome scholarly look at the impact of the First Family of Country Music (some of whose members remain active today, though the original incarnation of the band lasted only from 1927 to 1941). The Carters have a rich legacy on country, gospel and folk music alike, and Zwonitzer does a good job—though by no means an exhaustive one—of exploring that legacy.

Gayden Wren, entertainment editor for the New York Times Syndicate, is also a country singer/songwriter as Tennessee Walt; visit TennesseeWalt.com for details.

FURTHER READING

Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, by Barry Mazor (Chicago Review Press, 2015).

Peer was a pioneering A&R man and music publisher, there at the dawn of the country music industry, including the first country recording sessions with Fiddlin’ John Carson in 1923 and the discovery of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family at the famed Bristol sessions in 1927.

Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the age of Jim Crow, by Karl Hagstrom Miller (Duke University Press, 2010).

A look at the early days of the recording industry, specifically how music was categorized and marketed to racial and ethnic identities. Miller argues that these categories bear little relation to the ways that southerners actually played and heard music.

Hear My Sad Story: The True Tales That Inspired "Stagolee," "John Henry," and other Traditional American Folk Songs, by Richard Polenberg (Cornell University Press, 2015).

Several songs featured have been recorded by country musicians, and some have become standards in the bluegrass field.

The Spirit of the Mountains, by Emma Bell Miles (James Pott & Co., 1905).

The chapter "Some Real American Music" first appeared in Harper's Magazine in 1904. Nick Tosches called it “the most beautiful prose written of country music....perceptive and bare of misknowing romance," and "a captivating eerie thing."

Where Dead Voices Gather, by Nick Tosches (Little Brown, 2001).

A look at the life and legacy of Emmett Miller, a mysterious blackface entertainer whose records influenced Merle Haggard, Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, and Bob Wills. The book features Tosches' usual heroic digressions.

The Nick Tosches Reader, by Nick Tosches (Da Capo, 2000).

Includes excerpts from Tosches' book Country!, his biography of Jerry Lee Lewis, and an excellent long profile of country singer George Jones.

Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia, by Fiona Ritchie & Doug Orr; foreword by Dolly Parton (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

A close look at one of the many roots of what we now call country music. Includes a CD with recordings by Dolly Parton, Doc Watson, and more.

Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany, by Charles Portis; edited by Jay Jennings (Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 2012).

Portis is the author of True Grit and comic cult novels like Dog of the South. Escape Velocity includes an entertaining 1966 Saturday Evening Post essay on country music.

For more books of interest, see Head of Events Sara Holliday's book recommendations article Guitar & Pen: Books on Popular Music & Musicians.

For authoritative reference material on music, see Oxford Music Online, available to members logged in to our website.