A Poet Bizarre: Hans Christian Andersen Before He Was Just for Kids

"All right! Now let's begin. When we reach the end of the story, we'll know more than we do now...." - Hans Christian Andersen, "The Snow Queen," translated by Tiina Nunnally

International Children's Book Day (ICBD) is celebrated each year on or near April 2, the birthday of Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875). Its center of operations is the International Board on Books for Young People, who also give the Hans Christian Andersen award every other year "to an author and an illustrator whose complete works have made an important, lasting contribution to children's literature."

Although ICBD is observed less in the U.S. than abroad, the dedication of the day and award to Hans Christian Andersen seems fitting, right? Everyone knows the Danish writer for his iconic child-friendly tales. I thought I did too, until I stumbled into a discovery many adult readers have made before me: We English speakers start from a seriously skewed view of Andersen's life and work.

Overshadowed

In part, this is due to the runaway success of the fairy tales, which quickly became family staples across Europe and North America. The tales may be the best of Andersen’s works, but they’re only the tip of the iceberg: his prolific output included novels, plays, opera libretti and song lyrics, poems, travel narratives, memoirs, and diaries. The Library’s holdings by and on Andersen hint at the actual breadth of his work and his centrality in 19th-century European cultural life. They also show why we who read in English are missing out.

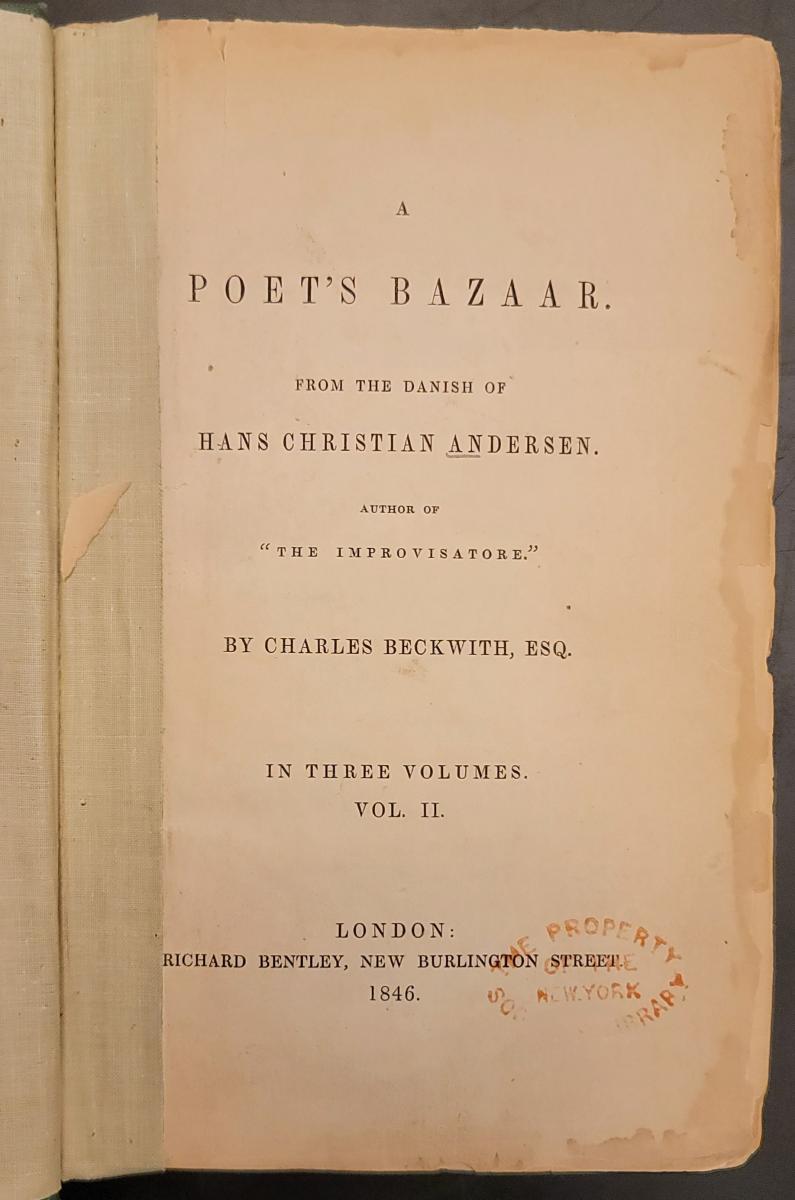

The Library has never heavily collected non-English-language books, and Andersen wrote only in Danish, so all our holdings come in translation. We acquired a couple of his travel books when he was yet a young man (including A Poet's Bazaar, 1846, shown here), along with three non-fantasy novels, The Improvisatore, O.T., and Only a Fiddler. The Improvisatore, a deliciously romantic big-canvas yarn set in Italy, was Andersen's big breakout, his international calling card for years.

Our copies are labeled “author’s edition” – i.e., editions that recompensed the writer in an era before any international copyright existed. Strikingly, they were translated by a woman, the English Mary Howitt. Unfortunately, Howitt was hampered by the bowdlerizing, bathetic tastes of the time. While Andersen could sometimes be mawkishly sentimental all by himself, his Danish critics usually tut-tutted at his brisk, informal, conversational writing – as shown in the "Snow Queen" lines above. That's hardly evident from Howitt’s stilted renderings, as in this apt passage from Only a Fiddler:

“When thy fingers had been blue with cold thou shouldst soon have come back again,” said Lucie.

“Thou dost not at all know me,” replied Christian. “In little things I am no hero, and I am not for that ashamed. But thou mayest credit me, I should like to be present when there was something really important in hand….I should think nothing of venturing my life in cases where anything extraordinary was occurring.”

Manden Som Can Fortaelle Eventyr (“The Man Who Can Tell Fairy Tales”)

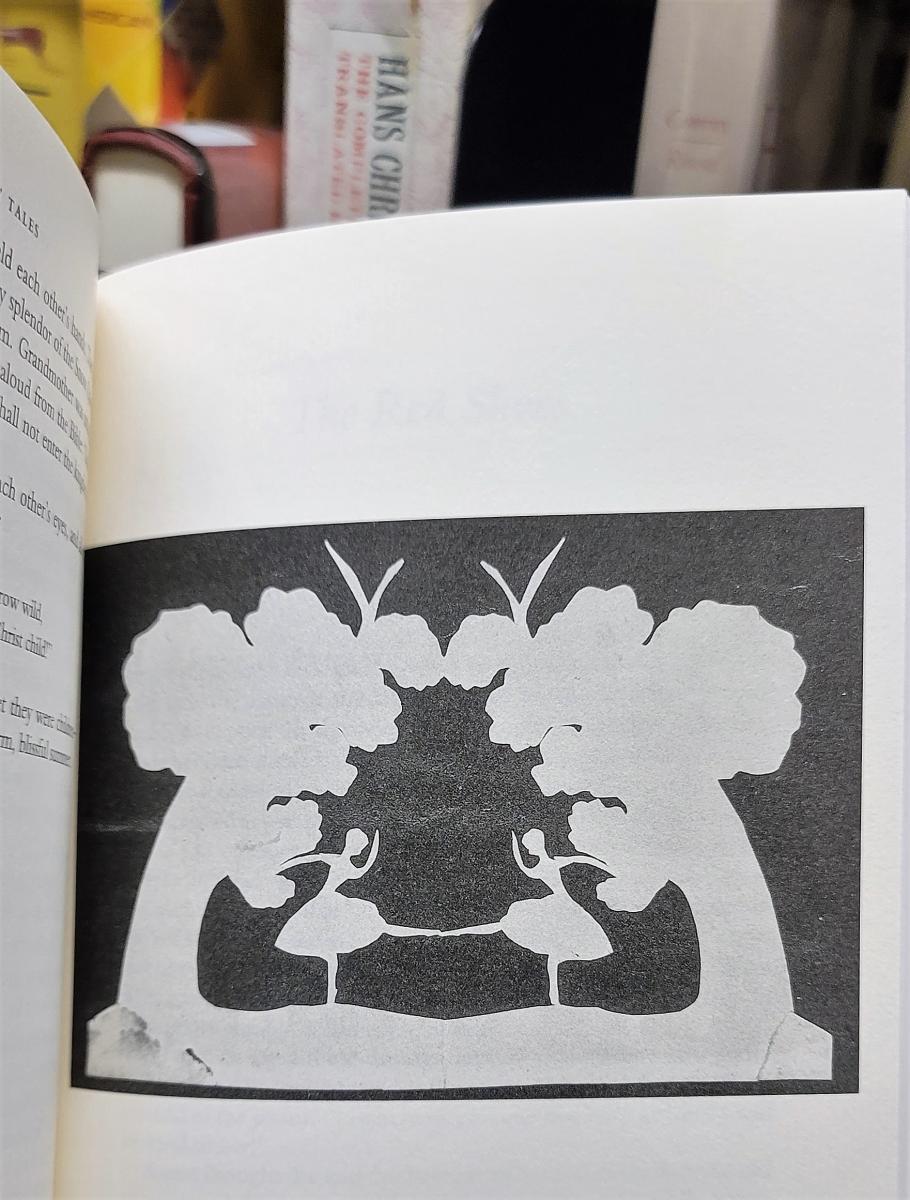

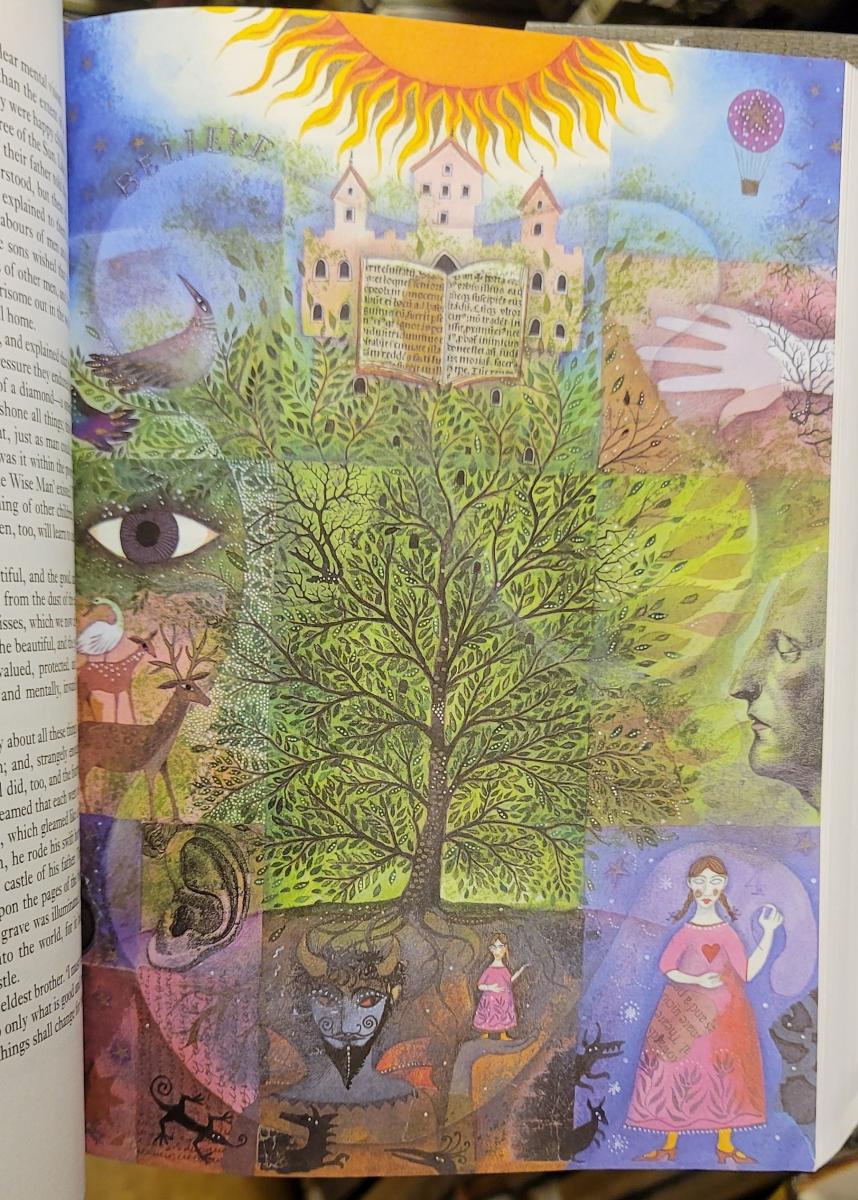

If the Library purchased any of Andersen’s fairy tales before 1900, they’re no longer in the collection. Once we hit the 20th century, though, there's little of his work other the translated tales and their adaptations - but lots and lots of those. That's despite their general bleakness of tone and stubborn lack of happy endings. When I dug into this 2005 selection translated by the gifted Tiina Nunnally, beautifully decorated with Andersen's own papercuts, I quickly found myself in places weird, wild, dark - and not what you'd call appropriate to the nursery. A prime example: "The Shadow," (1847), a brilliant, chilling story in which a man's shadow grows into an independent being and gradually takes over his life. Read it with no author name attached and you’d guess Edgar Allan Poe, M.R. James, maybe even Franz Kafka, never Andersen. Stack 3 also offers The Complete Stories translated by Jean Hersholt, including the tragic "The Wind Tells of Waldemaar Daae and His Daughters" and the nightmare-inducing "The Red Shoes" - but both common sense and universal cataloging practice label them Children's stories.

Our other fairy tale editions include

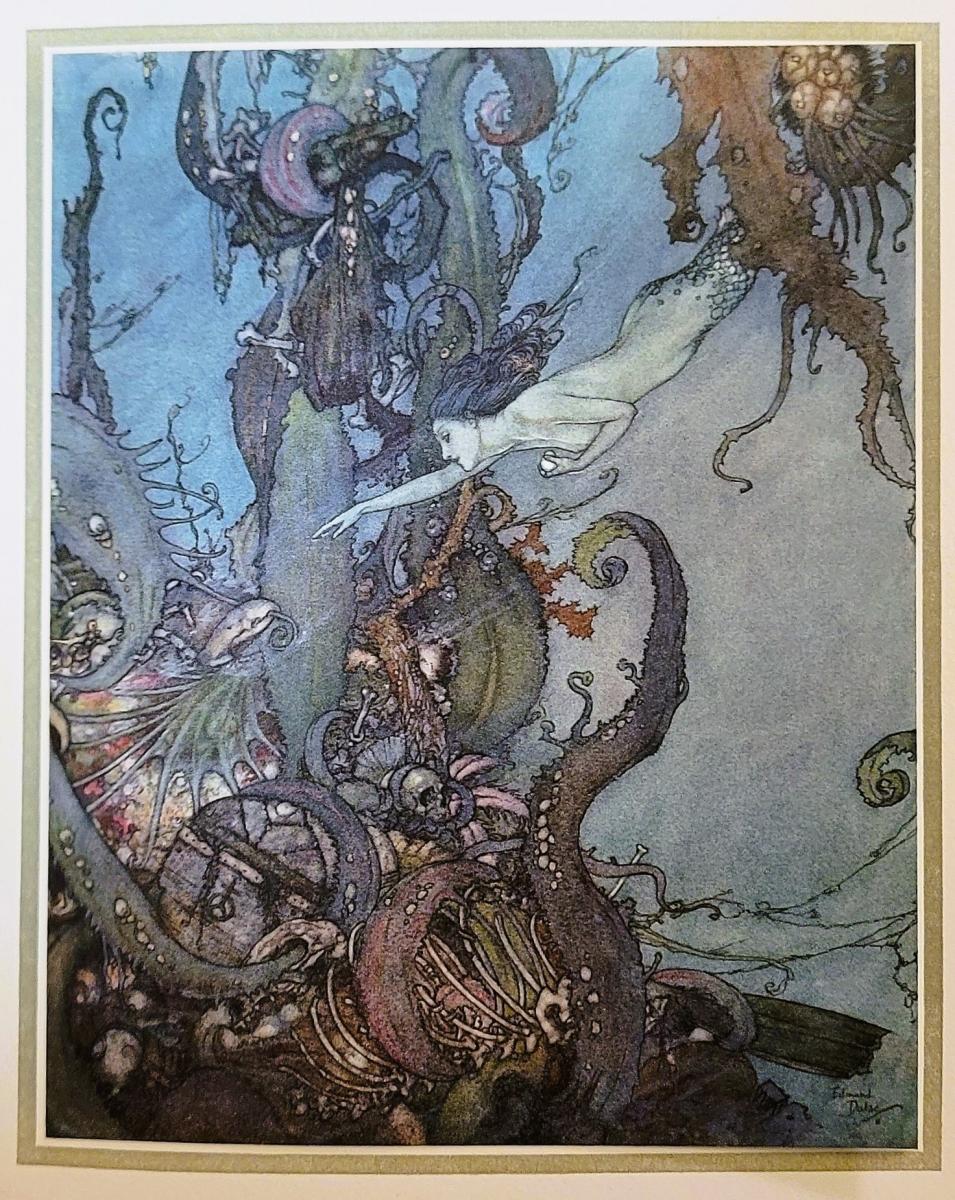

Stories from Hans [sic] Andersen, with illustrations by Edmund Dulac, 1911

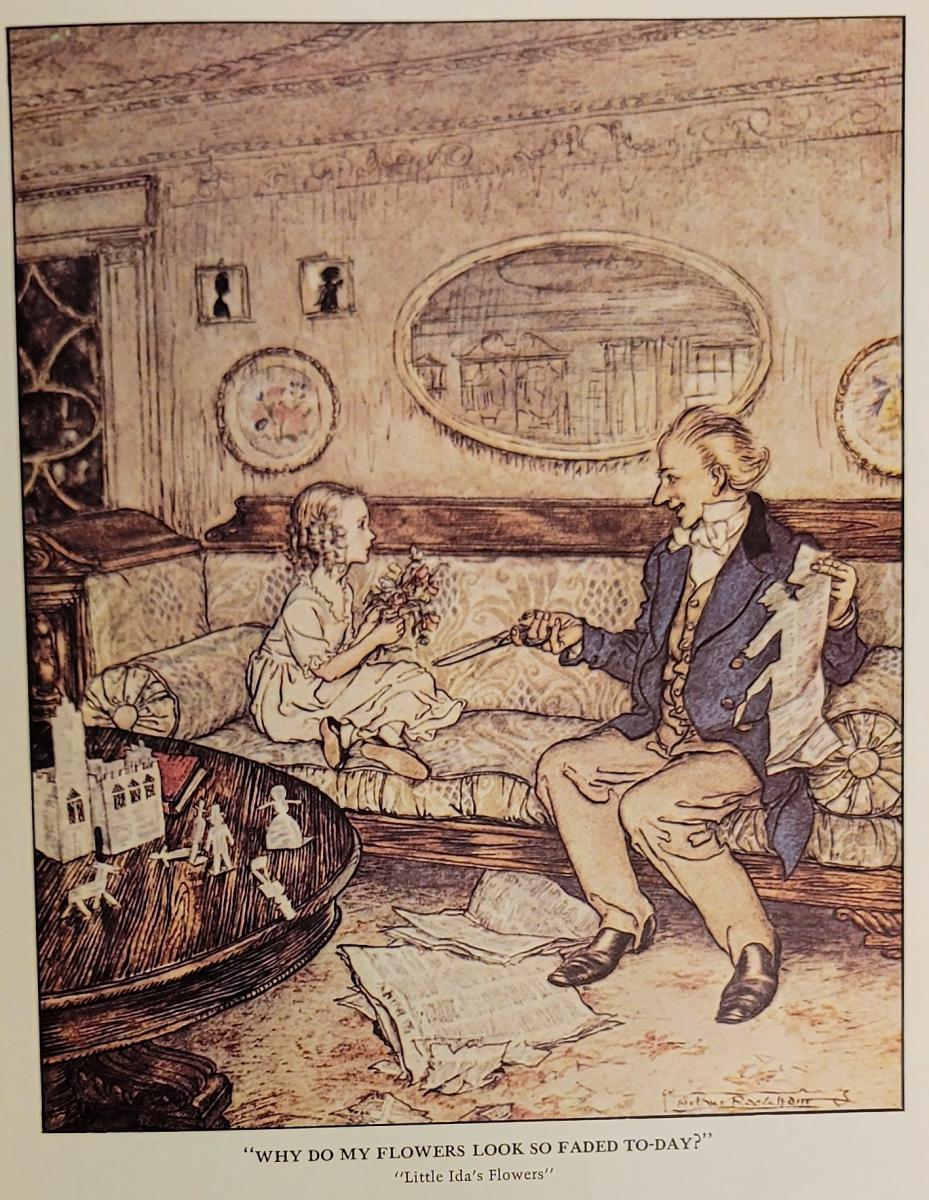

Fairy Tales, illustrated by Arthur Rackham

And, last but not least, Fairy Tales for Computers, containing a tale of E.M. Forster's alongside others' including Andersen's "The Nightingale."

We also have audio recordings of a selection of tales, read by an all-star cast.

These are just a few of the many diverse and excellent renderings of Andersen's short and fantastical works. But amazingly, the Victorian translations on our shelves are, with a few exceptions, still the only English-language versions available for his non-fantasy writings. And even his haunting miniature masterpieces have been overshadowed by kiddiefied adaptations. I too have been known to belt out ‘Part of Your World,’ but that doesn’t make the Disney versions good treatments of their source material.

Like many another artist, Andersen felt ambivalent about his smaller works swallowing up his more ambitious ones. He noted in a letter that his friend H.C. Ørsted (discoverer of electromagnetism) told him “that if The Improvisatore makes me famous, these tales will make me immortal, for they are the most perfect things I have ever written; but I myself do not think so."

Cold Climate, Hot Mess

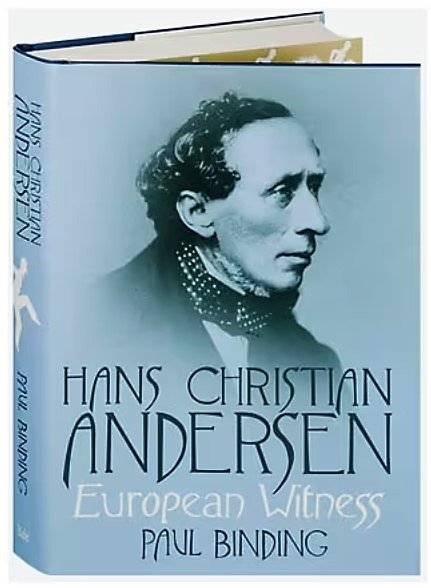

For a grown-up view of Andersen’s life and work, the Library does have a fortunate abundance of latter-day biography and scholarship, notably Jackie Wullschläger’s Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller (2000) and Paul Binding’s Hans Christian Andersen: European Witness (2014).

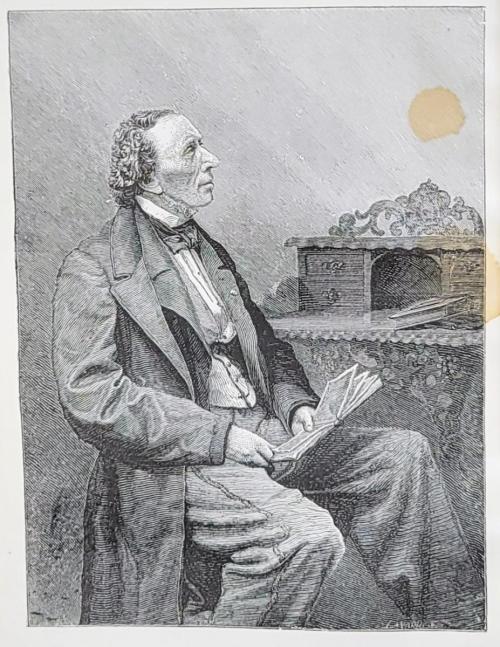

One of literature's true originals, Hans Christian Andersen (it’s “Hans Christian” or "H.C.," please, not plain “Hans”) pulled himself out of abject backwater poverty to create works beloved by common folks and kings. He dared to criss-cross Europe and bits of Asia and North Africa when even railroads were newfangled. He befriended his century's great thinkers, artists, and scientists, from Felix Mendelssohn and Jenny Lind to Alexander von Humboldt, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Charles Dickens (OK, sort of). He had towering ambition, a wonderfully open mind for his era, and obviously a magical imagination. Unconventional in appearance, manner, and interests, with high dramatic emotions and low street smarts, he might well identify with the experiences of autistic people today - and he suffered from anxiety and personal frustrations that would have kept a lesser being hiding under the bed. He clung to faith in his muse but often felt like an outcast - mocked, rejected, and desperately lonely. And who hasn’t at some time shared those feelings? though some people get much more than their due.

Those facts aren't necessary for an appreciation of "The Ugly Duckling" or "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," but they definitely enrich it. Andersen was his own flawed, struggling main character. His writings interrogated his life and psyche and portrayed cracked-mirror portraits of himself in a way that we now take for granted but that was cutting-edge in his time. The more personal he got, the more he described universal depths. That shows in the fiction but equally well in his first-person travel narratives and memoirs, packed with neurosis and fretfulness crowded in next to excitement, curiosity, humor, and awe.

Of a stay in Rome, Andersen complains, “The evenings were so lonesome in the cold, large rooms….All the doors were well secured with locks and iron bars; but of what use were they? The wind whistled and screeched through the crevices in the doors….If I would make myself comfortable, I was obliged to put on my fur-lined travelling boots, surtout, cloak, and fur cap….The evenings were somewhat long, but then my teeth began to give some nervous concerts, and it was remarkable how they improved in dexterity. A real Danish toothache is not to be compared to an Italian one.”

But contrast that with the adventure of climbing Mount Vesuvius during an eruption(!) in 1834: “To inspect a new stream of lava, we crossed to a place where the ground had freshly hardened, carefully though, because only the top crust was firm enough to stand on; through the cracks we could see red hot embers. Had the crust parted we would have been catapulted into that fire!” (Sample more in this post from The Marginalian.)

Don’t (seriously, don’t) go to the 1952 Frank Loesser/Danny Kaye film Hans Christian Andersen for any element of historical accuracy – except perhaps this passage:

“I’m Hans Christian Andersen – my pen’s like a babbling brook

Permit me to show you, dear sir, my very latest book

Now here’s a tale of a simple fool – just glance at a page or two

You laugh, ha ha! but you blush a bit

For you realize, while you’re reading it,

That it’s also reading you…”

And This Is an April Day

On Saturday, April 1, the Library is honored to be hosting the first major New York City event with the Human Library. This is a remarkable organization bringing readers together with human “books” who converse openly from perspectives that our society often treats with stigma or discrimination. Like Hans Christian Andersen, the Human Library was born in Denmark and has traveled the world. Surely Andersen – who greatly enjoyed his own fame – would be flattered that his birthday has become International Children’s Book Day. But I think the openminded traveler who loved to learn would endorse the Human Library just as passionately.

Hans Christian Andersen for Grown-Ups: A Starter Kit

A Story from the Dunes and Other Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, translated with an afterword by Paul Binding, 2018

Eerie, psychologically sophisticated, and occasionally hilarious, this is a beautifully translated selection of lesser-known short gems.

The Ice Virgin: A Novella by Hans Christian Andersen, translated with an afterword by Paul Binding, 2016

Gripping, haunting, tearjerking - should be the one Andersen work that everyone reads.

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, translated by Tiina Nunnally, edited and introduced by Jackie Wullschläger, 2005

An excellent selection of the tales, in a translation that feels both modern and of their era, and a visual pleasure to read.

Travels by Hans Christian Andersen, translated from the Danish and edited by Anastazia Little, 1999

A seamless compilation drawn from Andersen's voluminous travel books, memoirs, and diaries, translated like a ripping tale and full of adventure and misadventure.

or for just a taste of the travel narratives, there's the abridged, accessible

A Poet's Bazaar: A Journey to Greece, Turkey & Up the Danube by Hans Christian Andersen, translated from the Danish and with an introduction by Grace Thornton, 1998

and alongside those, you might enjoy

Just as Well I'm Leaving: To the Orient with Hans Christian Andersen by Michael Booth, 2005

in which Brit journalist Booth records his stunt journey along Andersen's longest route, encountering deceptive tourist traps, hot-rod nuns, and possibly a spiritual affinity with the author he's tracking.

Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller by Jackie Wullschläger, 2000

Winner of many awards, this is just a terrific biography - an insightful and compassionate portrait of its subject with plenty, but not too much, of his 19th-century world.

Hans Christian Andersen: European Witness by Paul Binding, 2014

The Wullschläger biography is the story of a life; this book is the story of an artist, with reader-friendly analyses of Andersen's works, their richness, contexts, and influences.

And to go with the big biographies, there's the sweet little

The Young Hans Christian Andersen by Karen Hesse, illustrated by Erik Blegvad, 2005

Captures Andersen's early years in both their deprivation and loss and their glow of wonder and creativity.

Have a favorite fairy tale to recommend? Spot an innocent error in this post? Email me.

Disqus Comments